Some fairy tales really are tales “As old as time,” which is the case with what we know today as Sleeping Beauty. Folktales from all over the world have parallels to this story (including the Norse mythology of Brynhildr) and historians have traced a path through many works of literature. The earliest written version was in Perceforest, an Arthurian Romance that featured a more racy version of the tale in the 14th century. Giambattista Basile had an Italian version of the story called The Sun, the Moon, and Talia from 1634. This version found itself in the hands of Charles Perrault, who in 1697 published La Belle au Bois Dormant (literal translation is “The Beauty of the Sleeping Forest”). Perrault’s telling is the most well known written version, but it is quite different from the Disney film, including a 100 year curse and the prince’s wicked mother attempting to eat his bride and their children. The Perrault version traveled from France to Germany and the story was updated by the famous Brothers Grimm in 1812 when it was known as Little Briar Rose.

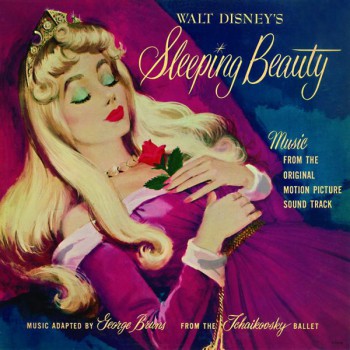

In Russia, the trio of Pyotr Tchaikovsky, Maurius Petipa and Ivab Vesevlozhsky adapted Perrault’s tale to the stage as a ballet called The Sleeping Beauty. The production was intended to be a throwback to court spectacles of the 18th century, which lacked a clear narrative but allowed Tchaikovsky to borrow that musical style for the orchestrations. The show opened on January 3rd, 1890 at the Marinsky Theater and was a flop. However, the music lived on and became popular outside of the ballet. This music is quite possibly what attracted Walt Disney to the story.

Development on Sleeping Beauty started at the studio in 1950. Many changes were made to the story, including twists unique to Disney’s version. Aurora now meets her prince before the curse through a memorable “boy meets girl” sequence, the 100 year curse was shortened to a single night, 12 good fairies became a trio, and the wicked fairy evolved from an ugly old hag into a beautiful and intelligent villain with a name nobody can forget, Maleficent. The story men felt that Sleeping Beauty spent so much time in development because Walt was distracted with live-action films, television, and Disneyland.

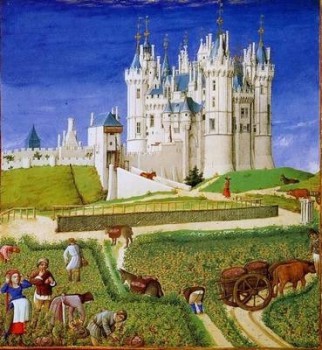

Walt’s vision for the film was that it would be “a moving illustration,” something he was adamant about. He assigned Eyvind Earle to create the style for the film and insisted that everything be consistent to his vision. Earle’s main source of inspiration was pre-renaissance European art. The film’s color pallette was inspired by Très Riches Heures by the Limbourg Brothers painted between 1412 and 1416. The castle depicted in their art was the inspiration for the design of King Steffan’s castle as well.

Tom Oreb was tasked with designing the characters that would inhabit Eyvind Earle’s world. They not only fit the style of the backgrounds, but also fit with the modern UPA style that had become popular in the 1950’s. Many of the animators felt Oreb’s designs were too rigid to animate with fluidity. Marc Davis, who animated Aurora and Maleficent, made tweaks to Oreb’s design of Aurora to suit the needs of making the character move. Milt Khal, who animated Prince Phillip, made similar changes to his character. In regards to Maleficent, Marc Davis takes sole credit for the design of the character. Early storyboards show that the Disney version of the evil fairy would be an old hag in bat-like attire. Davis was inspired by a renaissance painting where a woman’s headdress came to two points, like horns. He made the character beautiful and more interesting as a result. His original color choice for the interior of her sleeves was red, like fire. Eyvind Earle changed the color to purple to make it stand out more (Fauna was also yellow in much of the concept art before being changed to green).

When production first started in 1950, Walt hadn’t yet decided to use the Tchaikovsky score. Sammy Fain and Jack Lawrence were hired that year to write original songs for the story that was in development. However, by 1951 Walt had decided that Tchaikovsky was the way to go and handed them the main theme from the ballet. Sammy Fain protested, since he was a composer, not a lyricist, but Jack Lawrence pleaded that if this was all they would have to show for their time spent on the project, both of their names should be on it. That song was “Once Upon a Dream.” The song was used to help cast the voice actors. Mary Costa recalls singing it at her audition in 1952 (Walt called her that evening to offer her to role). Both Fain and Lawrence were reassigned to Peter Pan afterwards since Sleeping Beauty was delayed.

George Bruns was a composer hired by Disney in 1953 tasked with making the Tchaikovsky music fit the score of the film. While he went on to have a long career at the studio, Sleeping Beauty was the first project he was assigned to. He is famous for saying that it would have been much easier to have written an original score for the film. Tchaikovsky’s ballet was nearly four hours long, so selecting the right music for each scene was a challenge. Making the music fit the timing of the film was even more difficult. Tom Adair was hired in 1954 to resume writing lyrics for music that Bruns had identified as suitable to be sung by characters. He wrote the lyrics for nearly every other song in the film, the exception is “I Wonder” which has lyrics written by Winston Hibler and Ted Sears.

Animation on Sleeping Beauty took longer than most animated films for two reasons. The first is because the characters were so difficult to draw, resulting in less drawings per day from each artist. The second reason is that the film was made in one of the widest aspect ratios ever created, Super Technirama 70 (2.55:1). This required the use of bigger paper and a new approach to how scenes were laid out. With the wider screen, scenes had to be longer because you couldn’t cut to a closeup of a single character’s face. Animation production on Sleeping Beauty started around the same time as Lady and the Tramp. As a result of animating both female leads on Sleeping Beauty, Marc Davis wasn’t given an assignment on that film. Roy Disney was putting pressure on Walt to get the film finished faster. Walt’s solution was to setup cleanup team units that could get the drawings ready for ink & paint faster. In the end, actual animation on Sleeping Beauty lasted 5 years, but when you add the story development time, the studio spent nearly a decade on this film. The final cost to the studio was $6 million, making it the most expensive animated film ever made up to that point.

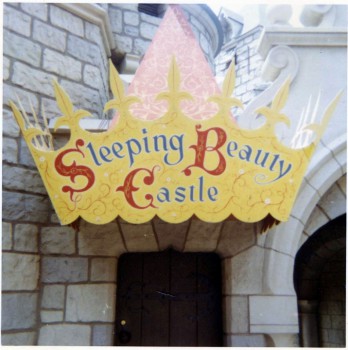

To advertise Sleeping Beauty, Walt did something rather risky. The centerpiece of his Disneyland park was a castle, originally to be named after the one that started it all, Snow White. But Walt saw the potential to sell guests at his groundbreaking theme park on his upcoming film and renamed it Sleeping Beauty Castle before its grand opening. At the time, it probably wasn’t obvious that the final film would take four more years to finish. An episode of the Disneyland series was also used to promote the film through a highly fictionalized biography called “The Tchaikovsky Story,” which aired on January 30th, 1959.

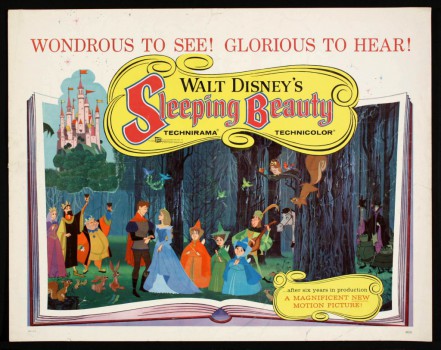

Sleeping Beauty premiered on January 29th, 1959, at the Fox Wilshire Theater in Los Angeles. Unlike Lady and the Tramp, which was filmed twice in widescreen and fullscreen to fit all theaters, Sleeping Beauty was only offered in widescreen (70mm Technirama or 35mm Cinemascope). Audiences who experienced the Technirama version also enjoyed 6-track stereophonic surround sound. Critics wrote mostly negative reviews, claiming that Disney was merely repeating themselves and drawing similarities to Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Cinderella. A few reviewers recognized the heightened art form and the majesty of the picture, but the general consensus was that Sleeping Beauty wasn’t good. In terms of box office gross, Sleeping Beauty was not a failure. It earned nearly $6 million and was among the top 10 highest grossing films of 1959. However, it did lose money for Disney since its earnings only covered the astronomical production costs. They lost an estimated $1 million on marketing expenses and the film didn’t turn a profit until its first re-release in 1970.

Like most of Walt Disney’s animated films, Sleeping Beauty went on to have a pretty incredible legacy. New audiences had the opportunity to experience the film as part of the studio’s rotation of films that were worthy of theatrical re-releases every decade. A walk-through attraction opened at Disneyland in 1957 to help advertise the film, but has remained a staple of Fantasyland for most of the park’s history every since. Two other Disney Parks are home to a castle inspired by the story. Hong Kong Disneyland’s Sleeping Beauty Castle is similarly modeled after Disneyland’s, but Disneyland Paris is home to Le Château de la Belle au Bois Dormant, which is a more stylized castle complete with square trees around the base in the style of Eyvind Earle. Aurora’s popularity has increased over the past decade through her inclusion in the evergreen Disney Princess franchise. The film is one of fourteen animated classics included in Disney’s “vault” release cycle, where each film is released every 7 to 10 years for a limited time before returning to the vault to await its next release.

Disney’s version of Sleeping Beauty inspired one of the most successful films of 2014, Maleficent, which puts a Wicked twist on the tale by making the mistress of all evil a heroine. Sleeping Beauty was last released in October 2008 as a 2-disc Platinum Edition Blu-Ray and DVD. It returned to the vault in January 2010 and was due for a reissue in October 2015, but due to the perfect timing of Maleficent the release was pushed up to this year. After nearly four years in the vault, it is “finally” being released again as a single-disc Diamond Edition Blu-Ray and DVD on October 7th. So for the four-year-old princesses out there, the wait is “finally” over.