Today marks the 50th anniversary of the premiere of Walt Disney’s most magical motion picture, Mary Poppins. To commemorate the occasion, D23 offered a screening of the musical fantasy in the Disney Studio Theater on Sunday, August 24. Joining in on the fun were Disney Legend Floyd Norman and historian Les Perkins.

Guests arriving at the studio in Burbank were directed to the Zorro parking structure, adjoining a section of the studio that had recently been demolished to make way for sorely needed parking. The walk to the theater took the crowd past sound stage number 2, the original home of Cherry Tree Lane. In 2001 the location was officially designated the Julie Andrews Stage.

It wouldn’t be a D23 event without a few treasures from the Disney Archives on display. The Hyperion Bungalow held a pair of cloth banners from the premiere, as well as a glass case with other artifacts from that memorable evening. Particularly intriguing was a letter, dated September 1, 1964, from author P.L Travers to Walt Disney, written to say THANK YOU (she used all caps).

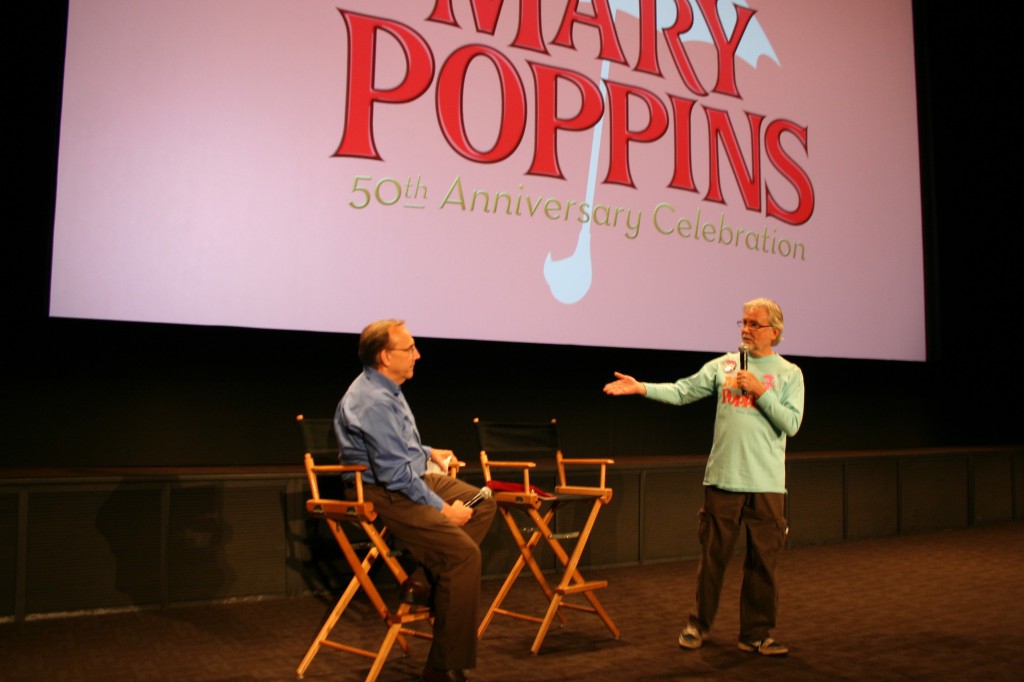

Once everyone was seated inside the theater, Kelly of D23 welcomed the crowd, and acknowledged all the familiar faces from the Faniversary Events held around the country. She then introduced a “surprise” guest, Disney Legend Floyd Norman.

Norman entered to an enthusiastic round of applause. He pointed out that the very first day of work on Mary Poppins had taken place in the building just next door to the theater, Stage A. The occasion was the first-ever recording session for the music. Norman recalled watching as music director Irwin Kostal, the Sherman brothers, Dick van Dyke and Julie Andrews began performing a lilting waltz that opened with an unusual lyric: Chim chiminy, chim chiminy, chim chim cheree. “We all knew then—magic was happening,” he stated.

He explained that for a musical, all the songs are recorded first, and then the actors perform to the playback on set. Animation was scheduled after the live action, meaning that the major part of his work was six to seven months from that first day on the recording stage.

Asked about the talent that had been brought in for the film, Norman recalled that he was particularly excited to meet Irwin Kostal, whose work he had admired on the Carol Burnett Show on television. Of course, he had met the Sherman brothers previously. They all had to wait to meet the talented Julie Andrews—Day One had been delayed for her to give birth to her daughter, Emma. The crowd agreed when Norman observed, “She was definitely worth waiting for.”

When Norman was asked if he had contributed any personal touches to the animation, he quickly pointed out that all the personal touches in Mary Poppins came from Walt Disney himself. “We all worked for Walt Disney,” he said. He did admit to having a fondness for the barnyard sequence in Jolly Holiday. He recalled putting animated farm animals on Dick van Dyke’s shoulders. He also spoke ruefully of his work on the pearlie band. There were no computer aids for animation in those days, and every single “pearl” had to be placed and animated by hand, frame by frame.

The subject of the recent film Saving Mr. Banks came up in answer to a question about what made Mary Poppins different from Disney’s other films. Walt was totally in love with the movie, Norman said, and that passion showed on the screen. In fact, Norman said, Walt had not been as excited about any other project since he had made Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. This excitement spread to the whole studio, as everyone pitched in creatively to realize Walt’s dream. “I don’t think there was a happier time in his life,” he said.

There was laughter as Norman recalled his first reaction to seeing the completed film—he admitted that after the long process of creation, he was pretty sick of it. As exhilarating as the experience had been, he was burned out, tired, and glad to be done with the job. Now it was time to send it away and give it to the world. And what a reaction! Norman proudly observed, “I’ve been a part of something very special.” He spoke warmly of realizing Walt’s dream, keeping a

promise to his two daughters, and creating a timely classic. He concluded, “You can’t ask for much more than that.”

Disney historian Les Perkins was next on the program. He discussed and presented rare behind- the-scenes film footage. With him was Tom Wilson, a film writer with special expertise about Julie Andrews. Perkins was visibly moved as he spoke of Mary Poppins, stating that along with Sleeping Beauty it influenced him to seek a job at Disney that began in 1973. The crowd reacted with oohs and ahs when he pointed out that the very first screening of the film had taken place in the very theater in which the event was held. Much of the final mixing had been done there, and Julie Andrews, Dick van Dyke, and Walt Disney himself viewed it there for the first time.

Perkins explained that there were 175 special effects shots, and that much of the footage had been stored away since the film’s first release. For the home video release he had tracked down much of the footage to show Julie Andrews to jog her memories of the film’s production. As they prepared to tape an audio commentary, Andrews recited sections of dialogue, and then noted, “I haven’t seen this movie since the premiere.”

Just before screening the footage, Perkins reminded the crowd that Mary Poppins was the culmination of all of Walt’s skills as an entertainer. It combined animation, live action, music, and even the new technology of Audio-animatronics.

The lights dimmed, and the crowd was treated to a series of oddly familiar scenes, shot in live action but without their familiar animated backgrounds. These had been prepared for the special sodium vapor process, developed by technical wizard Ub Iwerks, who won a special Academy Award for his work. The intense yellow lights and heat generated during the shooting took its toll—Matthew Garber could be seen wincing in some shots. After one slightly botched dance step, Julie Andrews playfully slapped Dick van Dyke. As David Tomlinson stood on a massive set of steps (the Fidelity Fiduciary Bank not yet added), he performed an amusing trick with his umbrella. Perhaps the funniest moment was seeing a stagehand feeding Mary’s hat rack up through the bottom of her “magical” carpetbag.

The lights came back up, and Les Perkins recounted a famous anecdote. During production of Mary Poppins Walt was perplexed to discover that everyone at the studio seemed to be happy. Perhaps, he mused, they finally realized that he was doing something right.

Tom Wilson told a story about one of Julie Andrews’ flying sequences. These special effect scenes had all been saved for the end of the shoot. At the end of one lengthy session, Andrews complained that something didn’t feel right with the rig. As they began slowly lowering her to the ground, she suddenly came loose and fell the last few feet to the stage floor.

He also spoke of a special photo shoot for Look magazine. The scene called for “Mary” to hover in the air, with Walt Disney sitting on a rooftop waving at her. As anxious teams fussed over Julie Andrews, Walt was left alone to clamber up a ladder unaided to his nearby perch.

Perkins then reminded the crowd that Walt had spent many years securing the rights to Mary Poppins. His first attempt was in 1937. In 1947 director Vincente Minelli announced he would make a live-action Mary Poppins. In 1949 a television production appeared, starring Mary Wickes in the title role. And in 1950 Hollywood legend Samuel Goldwyn announced he would be making his version of the story.

But, Perkins said, “It’s as though the universe waited.” He described the collaboration between Walt Disney, the Sherman brothers, Julie Andrews, Bill Walsh and Irwin Kostal as, “the greatest American fantasy film since the Wizard of Oz.”

Perkins recounted the story of how Walt “discovered” Julie Andrews and cast her in the film. It seems that everyone was trying to figure out who could play the pivotal role. One Sunday night, while watching television, Richard Sherman happened to catch a performance of a number from the new Broadway musical Camelot on a repeat of the Ed Sullivan Show. He was captivated by the young female lead, and called his brother Bob to recommend he tune in. Bob answered the phone exclaiming, “Are you watching Sullivan?”

The next day they went to the studio to sell producer Bill Walsh on the idea, only to find that he had seen the program, and wanted to sell them! Together they all headed up to Walt’s office, where they found his secretary already singing the praises of the same young lady she had also seen the night before on television. But, she warned, it was unlikely that Walt would be enthusiastic unless he believed he had found her himself. As he was already on a trip to New York City, she arranged to have a pair of tickets for Camelot sent to him. There he saw the lovely Julie Andrews, and decided that she was the perfect choice for Mary Poppins.

Just before showing footage of the original world premiere, Perkins and Wilson spoke of Poppins author P.L. Travers. Wilson pointed out that she liked several things about the film, including the change in time period from the 1930s to the 1910s, and the casting of Julie Andrews. While Travers felt she was too young, she did say that she “had the nose for it.” Travers ended up corresponding with Andrews, and even lobbied successfully to keep the song “Stay Awake” in the film. Travers also suggested Bert’s final line, saying that seeing Mary fly away with no hope of return was too sad.

The next set of film clips was a triumph of research, restoration, and creative editing. The premiere of Mary Poppins was the first ever “staged” for television. Sadly, no copy of the full TV broadcast has ever been found. There are many sections, in both color and black and white available. And a key discovery was a full audio track of the program, preserved in the Disney vaults. By carefully combining these elements, the crowd was treated to a simulation of that evening, fifty years ago. And then it was time to once again savor Walt Disney’s Mary Poppins.