Directors of Animation Then and Now

The Walt Disney Family Museum has become famous for attracting wonderful guest lecturers. On March 1st, Disney historian Don Peri and Pixar Animation director Pete Docter gave a presentation on animation directors. Their 2-hour presentation was very informative, on a seldom discussed topic that the audience seemed fairly unfamiliar with.

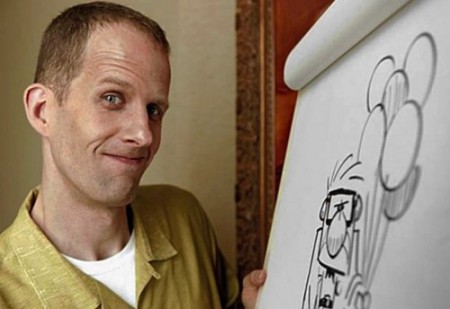

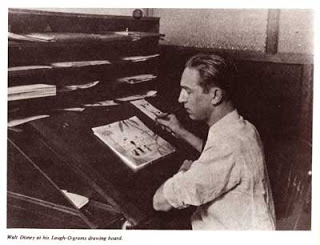

The presentation was given in three parts. The first part was about the directors' job. Pete Docter used a giant pad of paper to explain how at Pixar, the brain trust often develops the stories together. For example, he was part of the story team early on for Toy Story, A Bug's Life, and even WALL-E. However, Up was an original idea of his that went through many story changes in the process. Once the story is designed, a modern animation director takes it through layout & design, creating the world and character designs for the film with their team. Once all of the pre-production is done, the actual production takes place with voice recording and animation, all the way through post production with editing and release. Everything from start to finish is overseen by the director. John Lasseter oversees all animated films at Disney and routinely gives notes to the director, but these notes are suggestions, not mandatory like in Walt's day. Docter also shared that at Pixar, director success is only 50% with directors often being replaced before production is complete. Reasons for replacing a director are typically due to a lack of forward momentum. He stressed the importance for modern directors to create good relationships with the production crew and the executives, which is difficult to do. In Walt's time, Walt oversaw pre-production for every animated short and feature. His biggest contributions were in the story department, where everyone who worked with him admitted that he was a master storyteller. He gave final approval over all layout and design decisions as well. However, once pre-production was done the project was passed on to the director, or directors in the case of a feature. Walt viewed his directors more like associate producers. Walt's name appeared before every production, so if it was good he was known for getting all of the credit. When a film was bad, the director was held accountable. Walt hated directors who tried to take all of the credit due to the heavy team work required to produce animation. The second portion of the presentation was on the evolution of the animation director's role. In the earliest days of Disney animation back in Kansas City, Ub Iwerks was Walt's first director. Back then, Walt referred to directors as "story men." In 1928 after Charles Mintz stole Oswald and most of Walt's staff out from under him, he began to build a new team to start production on Mickey Mouse shorts. As the Hyperion studio grew, Walt's directors become more crucial to the operation. Walt was always big picture focused and his directors were responsible for filling in all of the details of the shorts.Walt was never satisfied with his directors, placing all of the blame on them when a production failed. Feeling that he could do better himself, Walt took the reins as director on a Silly-Symphony about King Midas called The Golden Touch. Because Walt was so focused on directing, he wasn't able to see the story problems with the short and it was a failure. Years later during an argument with director Wilfred Jackson, the unsuccessful effort was thrown in Walt's face. His reply: "Never mention that picture to me again." Walt never returned to directing, recognizing that his contributions were better kept to story.

Walt was outraged by his animation directors on another occasion. Under the belief that their contributions weren't substantial, he tried to produce a short without a director. The short was called Mickey's Amateurs and this experiment also failed. Walt had to admit that he needed animation directors, no matter how upsetting it could be to find that the final project didn't match the expectations during the pre-production that Walt oversaw. As the studio moved towards features, many of the most talented short directors were assigned to directing several sequences on the films, sharing director credit. Production units were created, featuring the director, story men, layout men, and song writers. The end goal for the directors on a feature was to produce Walt's film, not their own. Animated films always featured multiple directors until the 1960's.The story department in the early days at Disney used storyboards, which were invented by animator Webb Smith in the early 30's at the studio. Modern animation directors use scratch dialogue and story boards to form a leica reel (aka: animatic) so they can watch the film and work out the timing. In Walt's day, directors would sit with layout men and musicians to create the timing of the project. Each shot and action would be marked on exposure sheets. These sheets became a guide for the animators so they knew exactly how long their shots had to be and the action that needed to be completed within.

The final piece of the presentation was some revealing information on eight of the best animation directors from Walt's era. Little is published about these men, so here are some highlights on each: Burt Gillett - One of the early directors at the Hyperion studio, Gillett was the director of many Silly Symphony shorts during his time at Disney. His directing style was to give animators complete freedom over their characters with little interference. He directed The Three Little Pigs and claimed all of the credit for its success, angering Walt who saw many talented individuals responsible (including Walt's story contributions) and also attributed the success to Frank Churchill's song. When his Disney contract expired in 1934, Walt let him leave. He went to direct for an animation studio owned by RKO, which was dissolved when RKO signed a contract to distribute Disney's shorts. He found himself back at Disney for a short period of time, during which he directed Lonesome Ghosts.Wilfred Jackson - Jackson was hired by Walt two days after Carl Mintz hired his Oswald staff out from under him. He helped animate the earliest Mickey Mouse cartoons and introduced Walt to the metronome, the device that helped him create synchronized sound for Steamboat Willie. Walt promoted him to director when he couldn't keep up with the animation workload (Jackson expected to be fired, not promoted). One of Jackson's innovations at the studio was linking animators pencil tests into a film reel so he could watch the short and make changes before finalizing it for ink & paint.

Dave Hand - Hand was analytical, organized, and his directorial style was to delegate everything. Animators claim that if you put out great work, you found yourself with an unreasonable workload on a Dave Hand project. His first success was a Mickey Mouse short called Building a Building. Proud of himself after a screening, Walt knocked him down telling him how bad it was. He didn't understand it at the time, but looking back he says this drove him to become an even better director. Walt made him the supervising director on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and then promoted him to production manager, the second highest rank at the studio at the time (second to Walt). He was hired away to an animation studio in England in 1944 where he was unsuccessful as a director. Don Peri attributes this to the fact that at Disney, directors were shielded from all of the financial burdens directors face at other studios. Ben Sharpsteen - Sharpsteen was recruited to Disney by Burt Gillett. Shortly after arriving at the studio, he and Dave Hand developed a training program for incoming talent. When Gillett left the studio, Sharpsteen was promoted to directing the Mickey Mouse shorts. Animators described him as a father figure, giving out advice on everything from animation to which car they should buy. He was also a strict disciplinarian. Sharpsteen described Walt as an antagonist who took no excuses for a poor picture. He quickly figured out what needed to be done on his own versus what Walt needed to be involved for. He was the supervising director on Dumbo, where he famously cut four and a half minutes from the film, making it less than feature length because it made the film better. He eventually left animation, staying at Disney to direct the True-Life Adventures and People & Places series. He remained at Disney until his retirement in 1962. One funny anecdote shared is that when animators would check in to a hotel with a girlfriend, they would sign Ben Sharpsteen's name next to theirs.Ham Luske - Ham started at Disney in 1931 and remained there until his death in 1968. Luske was famous for asking his animators to add more "Ooooooh!" to their scenes. In other words, make them cute. Those who worked with him say he was one of the few directors who could read between the lines of what Walt said versus what Walt meant. During production on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Luske was so involved in the character of Snow White and making sure the animators were consistent that Walt rarely gave any notes on the character, instead focusing on the supporting cast and animals.

Clyde Geronimi - Geronimi was famous for keeping his productions on time and on budget. He had a rare talent for being able to demand quality when time wasn't an issue and speed when it was. He is responsible for two of Disney's Oscar wins for the remake of The Ugly Duckling and Lend a Paw. He remained at Disney through the 1950's and took over production on Sleeping Beauty when that picture went over on time and budget. The reason Sleeping Beauty cost so much and took so long was because the directors were listening to all of Walt's suggestions. Geronimi had a knack for knowing what advice from Walt to keep and what to ignore. He left Disney briefly in 1959 to work for UPA, but came back midway through production on One Hundred and One Dalmatians.Jack Kinney - Kinney was known for being fun and a bit of a "screwball." He directed the Goofy series of shorts and was the inventor of the "How to" concept when Pinto Colvig quit doing the voice. Instead of planning out the timing ahead of time, Kinney would let his animators explore their scenes and hand him their pencil tests. He would cut the film together to determine the pacing and then reassign scenes to animators. His directing style was fast and loose and unlike his fellow Disney directors at the time, Kinney made many contributions to the story department. He never got credit for this, however, because Walt didn't believe in giving multiple credits to individuals on a picture. Don Peri says that the "least-Disney" shorts were directed by Kinney. Woolie Reitherman - Reitherman placed animation first above story. He rose through the ranks as an animator on Jack Kinney shorts, where his specialty was action animation. Walt Disney trusted Woolie's judgement and believed he had his finger on the public interest. He was the first person Walt assigned to be a single director for an animated feature when he was given total control on The Sword in the Stone. He liked to explore scenes to an exhausting level to make sure they were right. Many animators disliked working with him due to his preference for reusing animation in films to speed up production. One of his biggest contributions to the studio came after Walt's death, where he was responsible for stabilizing egos and talent while the studio was without a leader to keep the peace.

What emerges from this presentation is an image of a group of men dedicated to their craft trying to find balance in a world lead by Walt. It is clear that Walt wasn't easy to work for, but his methods were successful in producing quality films that have remained fresh longer than anybody could have anticipated. The role of an animation director at Disney grew considerably, but under Walt's leadership they were making Walt's films, not their own. After Walt's death, the studio struggled to find itself for a while before the right teams were in place to revolutionize the industry again.

In the modern Lasseter era, the emphasis is on creative freedom as long as there are strong characters and unique worlds behind each film. Lasseter's leadership style creates a democracy and a brain trust ensures that multiple opinions are weighed before moving forward with a project. Directors are often changed out midway through to keep momentum moving, and modern technology makes it easier to make changes on the fly if something isn't working. But it is clear that today's animation directors owe some credit to those that came before them and made the medium what it is today.Alex is currently watching and reviewing all of Disney’s films in chronological order. You can follow along here.