Alice Through the Looking Glass: Using “Previs” and “Postvis” in VFX Filmmaking

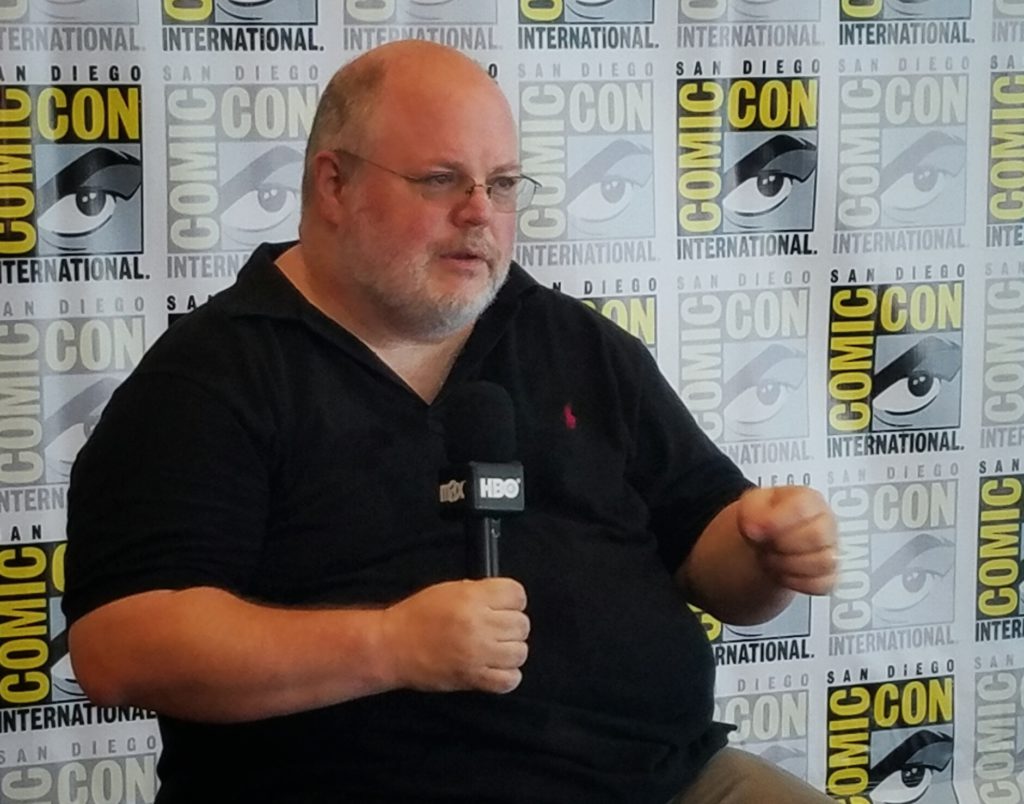

One of the opening panels at San Diego Comic-Con featured the visual effects team that created Alice Through the Looking Glass, set in the world of Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland (2010). Ed W. Marsh (VFX Editor and Stereoscopic Supervisor) and HALON Entertainment’s Tefft Smith II shared their filmmaking experience in the panel: “Feed Your Head: The VFX of Alice Through the Looking Glass.” Tefft and Ed were proud to be part of the vast teams of artists and technicians who realized the imagery for the film. I was also privileged to sit down with them after the panel.

Director James Bobin (The Muppets) brings us the story of Alice Kingsleigh (Mia Wasikowska, Alice in Wonderland), based on the original characters by Lewis Caroll, set three years after the last film. Alice is an accomplished sea Captain escaping pirates but returns to London to find that the world still will not accept her for who she is.

Alice is called by Absolem (Alan Rickman, Harry Potter), the blue caterpillar-turned-butterfly, to help Tarrant Hightopp, “the Hatter” (Johnny Depp, Pirates of the Caribbean). “You’ve been gone too long, Alice. There are matters which might benefit from your attention. Friends cannot be neglected…hurry.”

The panel was treated to never-before-seen alternative footage of Absolem speaking with Alice, discussing the kidnapping of the Hatter’s family, the Hightopps. This was the last role that Alan Rickman played before he passed away on January 14, 2016.

Alice returns to Underland to help her friends. Here she meets Time (Sacha Baron Cohen, Les Miserables, Sweeney Todd), and steals his Chronosphere to change history and save Hatter’s family.

VFX Example: Capture of the Hatter’s Family, the Hightopps

Marsh and Smith demonstrated the visual effects filmmaking process, showing final footage of the Hightopp family capture on Horunvendush Day by the Red Queen Iracebeth (Helena Bonham-Carter, Harry Potter) using her fire-breathing Jabberwocky.The team then showed the same scene in various stages: from “previs,” blue screen, “postvis,” and the final footage.

“Previs”

Previsualization (“previs”) allows the filmmakers to “test visual effects” and “allows us to do fast iterations” before even shooting the scene. Previs helps with the filming budget, helping directors test different camera angles and lighting for the scene before any actors or crew are on set.Google Earth images are used to build sets of actual filming locations before any cameras start rolling. Main characters have digital models that move through each scene. With clear previsualization, the camera crew, actors, and producers know what the director is planning before shooting any particular scene.

Modeling a scene in previs takes approximately one week, says Tefft. Increasingly, directors are using previs as a guide before filming.

Using the “Techvis” program, visual effects teams can create 3-D modeling for key visual effects. Techvis uses specific camera lenses, shooting angles, and understands the relationship of the camera to the actor and the environment.

Aerial and wide-angle shots can be programmed with Techvis models of the actors. It models real heights (so the proper size camera cranes can be prepared) with real camera lenses (24 mm, 50 mm, 75 mm) to achieve the desired shot.

The software understands that in a room with given dimensions, the camera and the cameraman’s space need to be accounted for to achieve the shot desired by the director. This reduces delays and means less guess-work on the set.

With these technical aspects out of the way, the has director more time to inspire the best performance from their actors. Actors also benefit from previs, getting a clearer picture of what the director wants for the scene.

Film clips shown had effects editorial notes like “add motion blur.” Marsh and Tefft explain that this scene was filmed in Slo-Mo, so playing it at regular speed did not create the normal sense of motion.

Cameras, Action! Live on the Blue Screen Set

Amusing blue screen footage was shown, with Alice running and falling on the blue ground in a blue room. Blue bodysuit people then took away the Hightopp family (standing in for the Red Queen’s Card guards).Iracebeth jumps onto a crane platform that stands in for her Jabberwocky. She is holding a blue prop that stands in for her tiara. Apparently, the final tiara prop was not ready because of changes in design. It was easier to create an entirely CG tiara than change a physical prop she was holding.

Tefft Smith II on “Postvis”

Once the scene is shot with the actor, post visualization applies the special effects planned to see if the combination works. Tefft described his responsibility was to “fill in the blue” screens with digital effects. Once he started working with the director on Postvis, the collaboration allowed the ‘ability to just create…a new world.”

The director wanted 800 essential shots digitally mapped in three weeks. Smith’s team of artists at HALON completed 1,274 postvis scenes in three weeks, just in time for an early screening of the film.

Tefft was an expert in managing how many key artists he would need depending on the CG needs for each scene, based on an estimate of three to fice shots per artist per day. At times when there was more intensive work, his staff would expand from five to 12 artists.

Smith described how, as a joke during a screening, he had replaced two frog characters with two Kermit the Frogs. He got quite a laugh from the team. While it was hard work, they still managed to have fun. But no, they didn’t make it to the final cut.

They were also encouraged to be creative. “Make it better.” “Make it cooler.”

Ed W. Marsh on 3-D Conversion, Depp, and Story development

Marsh described Johnny Depp and Sasha Baron Cohen as ‘two of the greatest improvisational actors’ today. They did not want 3-D filming to get in the way of the actor’s performance. The best directors just ‘put them together and let them go’ (as seen in the Hatter Tea Scene). Some of the takes lasted 8 to 12 minutes at a time, “shooting it like it was an improv”

When asked to describe a production story we might not have heard about Alice Through the Looking Glass, Ed Marsh described an element of story development. They were trying to decide how the Alice and the Hightopps could be rescued from the Red Queen.

In early storyboards, the Bandersnatch would come in and charge the guards, vegetable people inspired by the fruit/vegetable portraits of Italian painter Guiseppe Arcimboldo. Cucumber slices would go flying across the screen “like Benihana.’

While this was visually interesting, another idea came forward. The Red Queen’s handmaiden was also a vegetable creature. Earlier in the movie, the Red Queen broke off her handmaiden’s radish nose and ate it. The handmaiden, of her own free will, decides to free Alice from the jail.

Ed described this as “harvesting character,” creating depth in an already introduced character to forward the story. It showed that creatures in Underland had free will and exhibited differences of opinion.

Hope you enjoyed these behind the scenes moments with the filmmakers! What is your favorite moment from Alice?