Interview: Author Dave Bossert on the History of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit

David Bossert is a man who knows a thing or two about animation. After graduating from the famed California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), Bossert started his career at the Walt Disney Animation Studios. Over the years, he's worked on such films as Beauty and the Beast, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and Fantasia 2000 among many, many others. He's also written extensively about the artform and other topics in books like Remembering Roy E. Disney: Memories and Photos of a Storied Life and Dali & Disney: Destino: The Story, Artwork, and Friendship Behind the Legendary Film. His latest book, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit: The Search for the Lost Disney Cartoons, hit store shelves earlier this week.

Recently, Alex had the chance to chat with Dave about his new book, the history of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, and what differentiates the character from Mickey. (Note: to hear our full interview with Dave, tune into the Laughing Place Podcast).

Alex Reif: This book's really amazing. It opened my eyes personally. Obviously, as a Disney fan, I know the history of Oswald and the basic Cliffs Notes version of the story. So I was wondering if you could give us a little more kind of backstory on the worldwide popularity of Oswald and then his longevity over the years.

Dave Bossert: Sure. You know, one of the things that a lot of people don't realize is that they were making 16-millimeter prints of all of these films, not just the Oswalds, but other silent films, for home rental. It was an early way of home entertainment, really. People could rent these 16-millimeter prints and run them in their houses. So, you had a lot of these prints scattered all over the place and Europe was a big market for the Walt Disney Company in the late '20s and especially into the 1930s once Walt was really up and running with the Mickey Mouse cartoons and the Silly Symphonies. They were driving about a third of their revenue from the European markets, and that, when the war broke out over in Europe in the late 1930s and then the US got involved in the early 1940s, there was a huge chunk of revenue that disappeared for the company and it created some financial issues for them and they wound up taking on a lot of government contracts to do training films and public service announcements and those kinds of things.

So, Europe was a very important part of the revenue stream for the company.

AR: It's just interesting, some of the places that some of the shorts turned up. At the back of the book and throughout the book, you do give a really great overview of each individual short, what it detailed, all the gags and bits in there and the story elements, artwork when it's available. But there are, I think it's eight shorts that are completely missing still. Is that correct?

DB: There's seven.

AR: Seven?

DB: Yeah. So, when they repatriated Oswald back, the original 26, and at the time they believed there was 26 and my colleague David Gerstein had uncovered a 27th called "High Up" that has Walt's name on the title card, and we talk about that in the book a little bit. But the 26 that Walt Disney created is what was repatriated back to Disney. Of those, there was, I believe Universal only had six prints of six different titles, and they wound up getting another seven cartoons from the collector world. So, there were some terrific people out there that had, in private collections, had prints of other titles. So, altogether they had 13 titles, which is what you saw on the Treasures Edition that was put out not long after they repatriated those cartoons back to the company.

So, there were the other 13 missing and when I got involved with it in 2011, we wound up finding another six titles and many of those pretty much came from the European arena. And thanks, in great part, because of the work that David Gerstein had done.

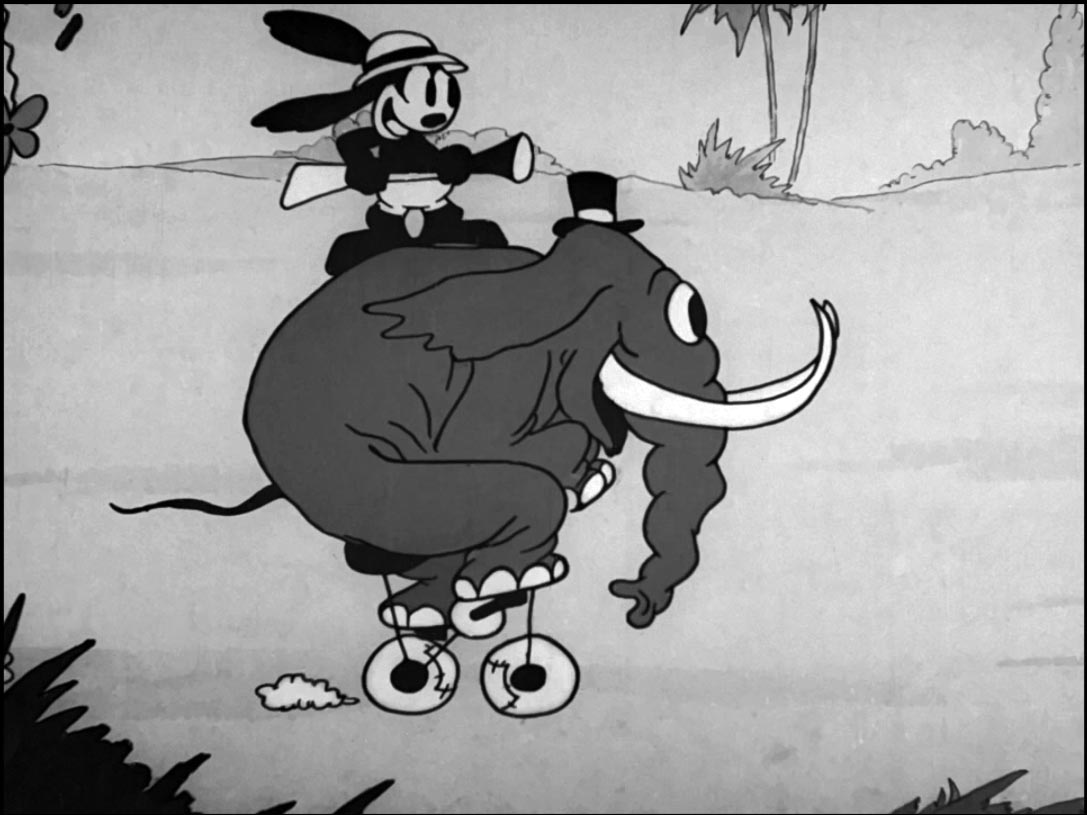

A still frame from the Oswald short AFRICA AFTER DARK, ©Disney

AR: That's awesome. And just curious, so there are these seven shorts out there that we have zero elements of, and then I think there are four shorts that are incomplete — like we're missing some elements — that Disney has in their vault. Do you have any gut feelings or leads on where these could potentially turn up around the world? Like, if anyone international is listening and knows somebody.

DB: Yeah. A lot of these are turning up in national film archives. There have been some that have surfaced in private archives, but for the most part, "Africa Before Dark", which was a beautiful element. It was a nitrate 35-millimeter print that was at the Austrian Film Museum when it was found, and that cleaned up just beautifully. It had a German title on it, so nobody really quite knew what they had all those years that it sat there.

And if you look at the back of the book, we actually have a page dedicated to those missing shorts, and again, thanks to David, we have French, German, Spanish, and Dutch titles listed underneath each one of the missing shorts, so that in the event somebody out there in an archive gets ahold of the book and looks at it and says, "Gee, that sounds familiar," they may have it.

My belief is that there are copies of those missing cartoons some place. I don't want to believe that they're completely lost to time, and I also will tell you and your audience that of the seven that are missing, we actually have identified one.

AR: Oh, wow.

DB: And we believe we know where it is, and it's a matter of being able to get digital scans of it. So, that's something that's on my radar.

AR: You mentioned "Africa After Dark," which I think was recently released on the Pinocchio Walt Disney Signature Collection release, and a couple of these other ones, Hungry Hobos had come out recently through those. Are there plans? Are you willing to share anything about where some of these other shorts that have been acquired more recently might be accessible to fans?

DB: You know something, the "Africa Before Dark," I believe was released on the Bambi DVD, yeah. I don't work at Disney anymore. I left last year. So, I can't speak for them as far as what their plans are. I hope they have plans. I know that I've always had the goal of wanting to see all of the missing cartoons repatriated back so there was a complete set of them by the time the company celebrates its 100th anniversary. I think that the character is an amazingly important piece of the puzzle, because had Walt not lost the contract, he might not have created Mickey Mouse and we might not have a Walt Disney Company that we know today.

So, it's interesting when you think about those things, but as far as any future plans, I couldn't tell you if they have any plans in place to exploit all of these. I know I've had some conversations with Disney publishing about putting a special edition version of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit: The Search for the Lost Disney Cartoons out with all of the cartoons embedded in the book, similar to my limited edition version of the Dali and Disney: Destino. I think that would be a lot of fun to be able to have that for people to actually see the cartoons as well as have all the reference material in the book.

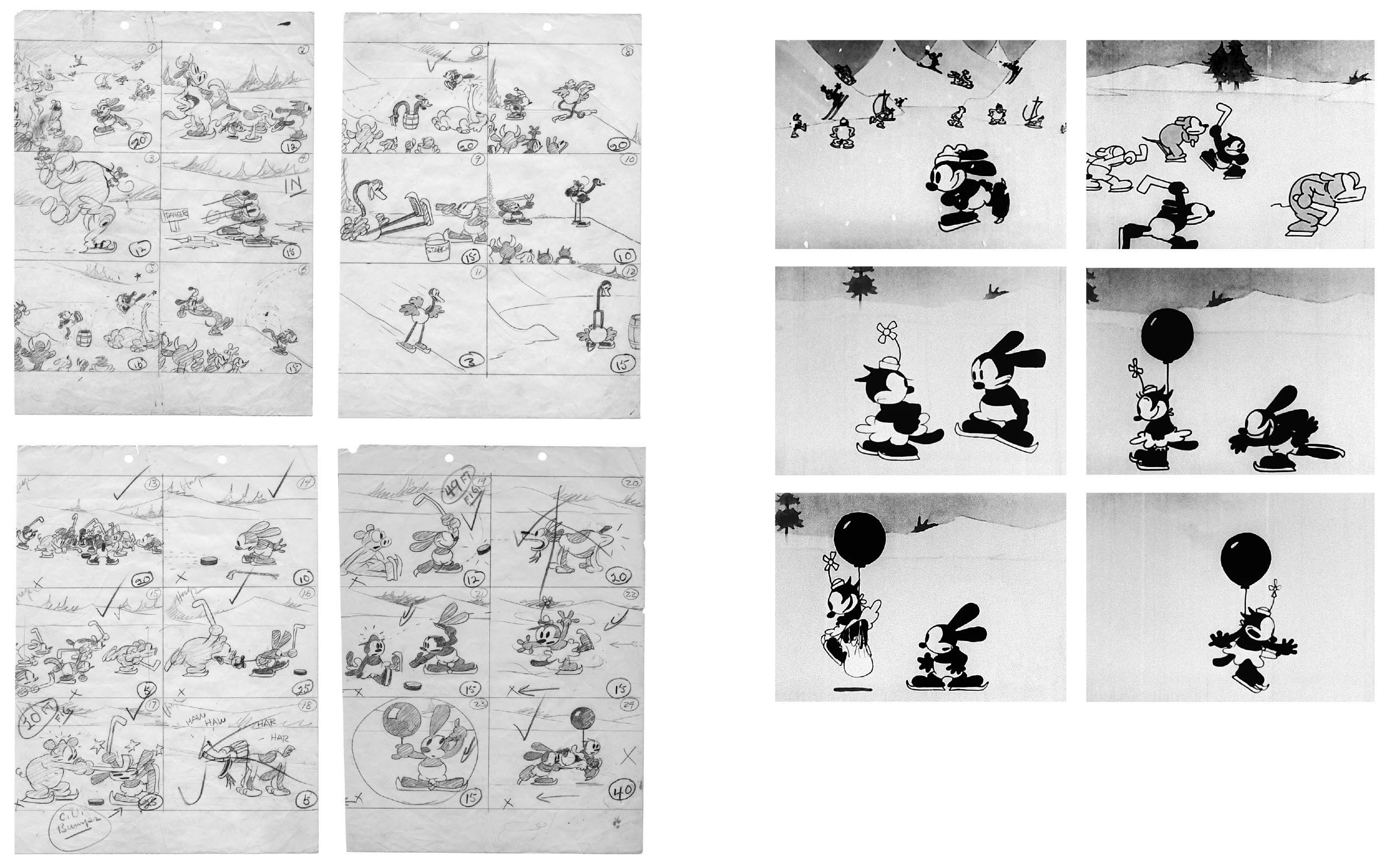

From a spread in the new book, a set of surviving story-sketch pages from Sleigh Bells that show the scene action in sequential order. This was the standard formatting for story sketches during this time, as the use of standalone storyboard drawings was not developed at Disney until the 1930s. Note that on some of these pages, and other story- sketch pages throughout this book, there are timing and footage notations, and in some instances the name of the artist cast to animate the scene is written directly on the drawings. Walt and Roy gave bonuses of $5 and $10 to artists for coming up with story and gag ideas.

AR: Growing up, Oswald was always the footnote to the creation of Mickey, because we didn't have access to it. Why do you think Oswald, who obviously was created before synchronized sound and the modern things that make us enjoy cartoons, strikes such a chord with the Disney fan base?

DB: Well, I think when you look at Oswald, he's a little bit more rambunctious than Mickey is. He's almost, it's like comparing The Rolling Stones and The Beatles. Oswald is a little bit more of the bad boy, in my mind, and I think that construction-wise, just his design is very similar to the early Mickey Mouse design. I think that he's fresh today, now that he's been repatriated back. You walk down, you go into the entrance of Disney California Adventure, you see Oswald's Garage. There's tons of merchandise. Oswald is actually incredibly popular over in Japan. The parks have added a walk around character and I think that he's just a cute, simple character. He's a cartoon. He's not humanoid. I think the fans are resonating to that.

Dave Bossert's new book, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit: The Search for the Lost Disney Cartoons, is now available Walt Disney Publishing. And for more of our interview with Dave, join us tomorrow and Friday for Oswald Week here on LaughingPlace.com