Interview: Star Wars Reference Book Author Daniel Wallace Discusses “The Lightsaber Collection” and More

Star Wars reference book author Daniel Wallace has been chronicling the goings-on of A Galaxy Far, Far Away since the late 1990s, when his exhaustively researched Star Wars: The Essential Guide to Planets and Moons was released. Since then, he’s written or contributed to dozens of other official Star Wars guides, not to mention plenty of books inspired by other fictional universes like Warcraft, DC superheroes, The Dark Crystal, Ghostbusters, Marvel, and more.

At the end of October, publisher Insight Editions released Wallace’s latest book that’s sure to become a must-own for fans of Jedi Knights and their iconic weapons-- Star Wars: The Lightsaber Collection, which enumerates the details surrounding a wide variety of the famous laser swords from everyone’s favorite space-opera saga. I recently had the pleasure of speaking with Daniel Wallace over Zoom to discuss his career, the process of creating The Lightsaber Collection, and his lifelong love of Star Wars.

Mike Celestino, Laughing Place: What was your relationship like with Star Wars before you started writing Star Wars books? I’m assuming you were a fan.

Daniel Wallace: [laughs] Yeah, that’s an understatement. I was a big fan. I started writing professionally for Star Wars back in the late 90s, so it’s been a long time at this point. It’s almost hard to believe, but the reason why I started writing for Star Wars is ultimately up to the fact that I really, really, really loved the universe. That goes back to being a very little kid and seeing the original movie. If you grew up later than I did, in a different era, there are a lot of different things that you can look to and say, ‘Wow, that’s really compelling. They’ve really done a good job in fleshing out the universe.’ Look at Harry Potter or you could look at Steven Universe or She-Ra or Spongebob. These are all things that have a pretty big fanbase, and a lot of it is based on the fact that the universes are very compelling. They’ve thought a lot about how things work and how the characters would inhabit this world, and what the relationship between the characters is.

And I feel like back in 1977 when the original Star Wars came out, it was like ‘What?’ They probably didn’t blaze that trail, but it was one of the very first things where you were like, ‘I love these characters. I love Han and Leia and Luke and I love how they’re interacting with each other. I want to see more of them, and I also want to know more about ‘how does this work?’ What is the Empire? Is there an Emperor? Everything you see raises more questions. I think the first Star Wars film just really nailed what’s compelling about a shared universe, and I’m so happy that so many other franchises have been able to achieve that since then, because I love these kind of things. But I feel like it was something else to be ground zero for that as a child, and I don’t think anybody understood it. I didn’t understand it. I was like, ‘Oh my god. Star Wars is the greatest thing I’ve ever seen.’ ‘Well, why?’ ‘I don’t know. I’m not sure why, but it’s the greatest thing I’ve ever seen.

And now as an adult, I’m like, ‘Well, it’s probably because of those things I just mentioned.’ They had really distilled those essences, and I think those franchises that I’ve talked about like a Steven Universe or something… that’s a pretty good example of characters that are interesting and a universe that raises more questions. You want to know how it works. And I guess if you were born ten years earlier than me, you might have said Star Trek with Captain Kirk and Uhura and Spock. But for me, it’s Star Wars. I’m a zealot when it comes to Star Wars. I don’t know what George Lucas did, but he just nailed the very first time. And the only thing that I can think of that even comes close prior to the 1970s is The Wizard of Oz. That came out in 1939, but everybody’s seen it. There’s literally nobody [reading] this right now who has not seen Judy Garland in The Wizard of Oz. And it was before your grandmother was born. There are very few fictional properties that nail that. Sherlock Holmes is probably another one. It’s like alchemy.

LP: How did you go from being a big Star Wars fan to actually writing official Star Wars reference books?

Wallace: I always feel a little bit apologetic when I answer that question, because people ask me that and they’re like, ‘Hey, you’ve done all these Star Wars books for decades now. How did you get started and could I get started in the same way?’ And the answer is ‘Probably not.’ [laughs] I feel like I was lifted by the winds. The reason why I wrote a Star Wars book in the first place, honestly, was that I was in the right place at the right time. I was an early adopter of the internet in the early 90s, and most people were not on the internet at the time. It rolled out later on. People read about the internet in Time magazine. They didn’t actually use the internet. But people who were into sci-fi and Star Wars were more likely to be in that, so a lot of the people that I was associating with on message boards at the time are now professional writers for Star Wars: Jason Fry, who I wrote The Essential Atlas with, Pablo Hidalgo, who’s a huge content manager over at Lucasfilm-- he was one of those guys from the message boards back in the 90s, and he got hired.

I’m being modest, but I think it’s fair [to say that] the only reason I got hired to write The Essential Guide to Planets and Moons is because I had written a text file called ‘The Star Wars Planets Guide. It was a guide to all the planets from Star Wars, because I thought, ‘Hey, this would be interesting for people.’ It had Tatooine and Dantooine and Alderaan, and at the time the Timothy Zahn Heir to the Empire books [and] the comics series Dark Empire had come out, so it included [those]. It was interesting to me. ‘Maybe people will want to download this and read it.’ And ultimately what happened was somebody over at Lucasfilm downloaded it and read it, and they were like, ‘This is literally the book that we’re planning.’ So they sent me an email: ‘Are you a flake?’ [laughs] ‘Could you actually write a book?’ And I was like, ‘Yes, I could write a book!’ And they were like, ‘We’re not convinced you’re not a flake. Would you mind submitting your resume and writing some sample pieces?’ A bunch of hoops, which to be fair was fully justified.

Then I luckily was able to jump through the hoops and they gave me the assignment to do The Essential Guide to Planets and Moons. And then luckily they liked the work, so the next book was [The Essential Guide to Droids], and after that was [The Essential Chronology]. It’s one-thousand-percent not a career path that you can replicate if you don’t have a time machine.

LP: More recently, what has the difference been contributing to Lucasfilm Publishing during the Disney era?

Wallace: It’s actually more similar than people think. For those who don’t know, the idea is that when Disney took control, the Expanded Universe at the time-- the spin-off books, comic books, various other subsidiary sources-- were deemed to be non-official. They were put into a category called ‘Legends.’ At the time, it wasn’t a huge shock to me and it didn’t bother me too much. It made a little bit of sense, because if you’re going to tell stories after Return of the Jedi and you want to hold the previous Expanded Universe as canon, there’s really not much you can do. It’s all been told. Prior to 2015, I wrote The Essential Chronology and The New Essential Chronology, and those books were designed to explain to fans what happened year-by-year after Return of the Jedi and what happened before A New Hope. They were history books. So you’d think I’d be really put out because I put so much work into those books, but I was like, ‘I get it.’

How are you going to tell a new story in an era where you have no white space to tell a new story? So that a-thousand-percent made sense to me. The other factor was I remember when the Disney acquisition actually took place. It was in the middle of when I was working on a book called Ultimate Star Wars, which is a Star Wars hardcover encyclopedia-- very nice looking book. I wrote it with a few other people. The announcement came in the middle of the writing process, so it was like, ‘Wait, what do we do?’

There were a couple examples that I remember asking Lucasfilm about at the time. If you’ve seen The Phantom Menace, you know that there’s another Yoda-like character-- her name is Yaddle, and she’s sitting on the Jedi Council. There was an old story about her backstory that was in a comic book. Then there’s also Greedo, the bounty hunter from A New Hope. I ended up asking Lucasfilm, ‘If we’re wiping out everything prior to the acquisition, does Yaddle still have the same backstory?’ ‘No, she doesn’t have the same backstory.’ ‘Okay. I think I get it, but for Greedo, if we’re wiping out backstory, is he still a Rodian from the planet Rodia and does he still carry a [DT-12] blaster?’ ‘Yes, he does.’

The distinction is that the narrative has been reset, but the tools that are in play-- the props-- [have not]. Imagine it’s a stage play, and the previous cast drops everything they’re holding and they take off their costumes and they leave them on the stage and they walk off. ‘Alright, here’s the new guys.’ They put on the same costumes and they carry out the same props. For somebody like me, who really just does lore, it was great. But I don’t want to minimize it, because there’s plenty of fans who were very invested in characters like Jaina Solo, and it stinks that you feel like your fandom has been minimized. I don’t want to sound dismissive to people who were very invested in certain storylines which are not going to continue, which is very true, but for people who are more invested in ‘What’s the nature of this universe? How does it work?,’ any of the homework you’ve already done prior to 2015-ish absolutely will pay off. You see that over and over again. You see that in The Clone Wars, you see that in The Mandalorian.

The Mandalorian is a great example. That, as a new series, is a-hundred-percent canon, it’s Disney-owned, and almost every 45 seconds, there’s something where you’re like, ‘I know what that is!’ It’s entirely built on the work that’s come before, which I think is the right way to do these kind of shows. It shows a respect for the history [and] the lore. And I don’t think that wiping out the previous stories is disrespect, because like I said earlier, I don’t think you could do anything else. You have to clear the slate a little bit [to] put some room for new stories. But I absolutely love The Mandalorian. I think it’s one of the best Star Wars stories I’ve seen in ages. Each episode is like, ‘Yes! They got it.’ You don’t have to turn your back on the world-building to tell a story, even though it’s under a new regime.

LP: That brings us to Star Wars: The Lightsaber Collection from Insight Editions. Where did the idea for this book come from? Is this something where you approach the publisher or they come to you wanting to do a book about lightsabers?

Wallace: I worked with Insight for a long time, but the real key to understanding the origins of The Lightsaber Collection is a book called Harry Potter: The Wand Collection. There was a book published fairly recently under that title that is the same format and the same concept, which is to take a look at the wands and the hilts of the wands from the films. The fascinating thing about the Harry Potter film series is it’s eight films, and there’s so many characters. There’s so many wizards and witches who use wands in those films, and you would think that at some point they would hit a point where they’re like, ‘Here’s the prop wand. We’re not actually going to design a new wand. It’s just a stick. Nobody’s going to see it. Who cares?’ And they never did. I can count on one hand the times you actually see a wand hilt in full detail. What does Fred Weasley’s wand look like? I have no idea. How would you even know? But they made one for him, and it makes sense. There’s a design philosophy behind them.

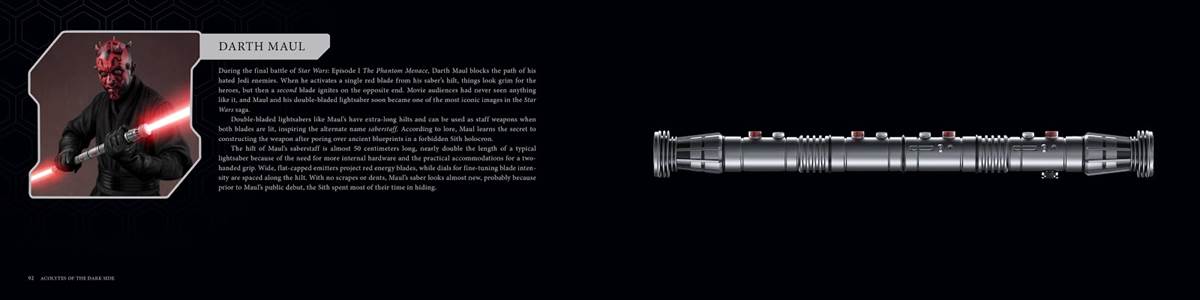

That was the impetus behind this book. Insight Editions did The Wand Collection. The obvious extension to this would be a lightsaber idea. They ended up talking to me about the concept, and I went through The Wand Collection like, ‘This would really work.’ Unlike Harry Potter wands, mostly what people associate with a lightsaber is the blade, but that’s not actually the most distinctive thing. The blade is interesting, but it’s usually blue or green or red. The hilt is super distinctive, and so I was like, ‘I think we could probably achieve something very similar. What are the design influences? Who owned this and what does the hilt say about them?’ In Harry Potter the wand chooses the wizard, and in Star Wars the hilt is designed by the Jedi. It’s a similar type of thing. You would expect that the exterior look of the weapon carries an aura of what the wielder is all about. And that was what I thought was the most interesting part of working on this book. I was very interested once I hit on that. ‘This sounds so cool. I can’t wait to get started.’

LP: The book contains a fairly comprehensive collection of weapons from the Star Wars movies, television series, comic books, and even video games. How did you decide which lightsabers made the cut and do you have any personal favorites that stick out to you?

Wallace: The final list of actual sabers was all over the place. We had an early list, and then to Lucasfilm’s credit, they kept coming back with suggestions. And every suggestion they came back with ended up making the book a little bit better. Most of the very unusual designs that you see in this book-- like The High Republic and the VR game called Vader Immortal, and a lot of sabers from the video game Jedi: Fallen Order, some from the comics-- came from Lucasfilm’s suggestions. They were like, ‘Let’s do a breadth of design influence,’ and it was smart, but that meant we had to remove some other ones and rearrange and do a lot of overall design work. I don’t know what the number is, but there’s only so many sabers we could include, so each one we wanted to include meant we had to delete one.

We tried to, as much as possible, have a breadth of visual influence, where if you were buying this you felt like you got your money’s worth. There weren’t two basically duplicate sabers in here. A lot of the lightsabers in the films were created as props, [like] I was saying earlier, so they had to be something that somebody could hold. Many of them you never actually saw in detail. Some of them were created as props for stunt actors to hold, so at some point along the continuum you move from a hero prop where it was very detailed and very unique, into a stunt prop where it was very practical. They would duplicate saber hilts. Not everybody in the background of Attack of the Clones has a unique saber hilt, because it was impractical.

So we looked at those and we were like, ‘If there is an instance where two Jedi that we know happen to be carrying a stunt hilt and it’s more or less the same design, let’s take them out of the book so that we can showcase something different.’ One of those examples is from the animated series Star Wars: The Clone Wars. There’s a Wookiee Jedi who Lucasfilm suggested including, because the lightsaber design is carved from wood. The lightsabers we’re familiar with from the movies are made from a metal cylinder with pieces of electronics glued onto it. This will help us show the range and the cultural variation that you would see if this were something that different people designed to be meaningful to them personally, and they all came from different backgrounds. That’s one example that we included in this book to convey the importance of the lightsaber as a personal expression.

LP: Can you talk about the two artists who contributed to this book: Lukasz Liszko, who did the lightsaber illustrations, and Ryan Valle, who did the character illustrations, and how their work complements your writing?

Wallace: Yeah, that was really the secret sauce of this. I don’t think that the most interesting part of this book is my writing; I think the most interesting or compelling part of this book is the renderings of these lightsaber hilts. The artists who worked on this book just brought it home and nailed that aspect of it. The biggest thing is you have movie props, basically, where you literally have an object that was built and designed in the real world to be seen on-screen. Then you have animation, where you have some sort of CG-type asset that was created for them. Then you have video games, where you probably have some of that-- there’s a little bit of variation. And we even comic book designs in this book, where maybe you have something to go on, but probably not much. You might only have one view; you can’t do a 3D turnaround.

The artists on this book took all that information and produced, when you page through this, they’re all utterly 3D, completely real, tangible artifacts. Even the ones from The Clone Wars or whatever, they have a level of veracity or tangibility to them, where you really feel like you could touch them. That was a tricky thing to do because a lot of the animation is designed to be a little bit stylistic. So they had a tough job, which is make that hilt look like it does in the show, but also make it look like you could pick it up. I think each and every rendition just nails it.

LP: Do you have any projects coming up next that we can look forward to?

Wallace: Yeah, I’m working on some projects right now. Some are Star Wars-related and some are related to other properties. I’m not really sure if I can talk about them yet. [laughs]

Star Wars: The Lightsaber Collection is available now wherever books are sold. The full audio from this interview has been featured in this week’s episode of Laughing Place’s Star Wars podcast “Who’s the Bossk?”