“101 Dalmatians” 60 Years Later – How a Spot-On Technology Saved Feature Animation

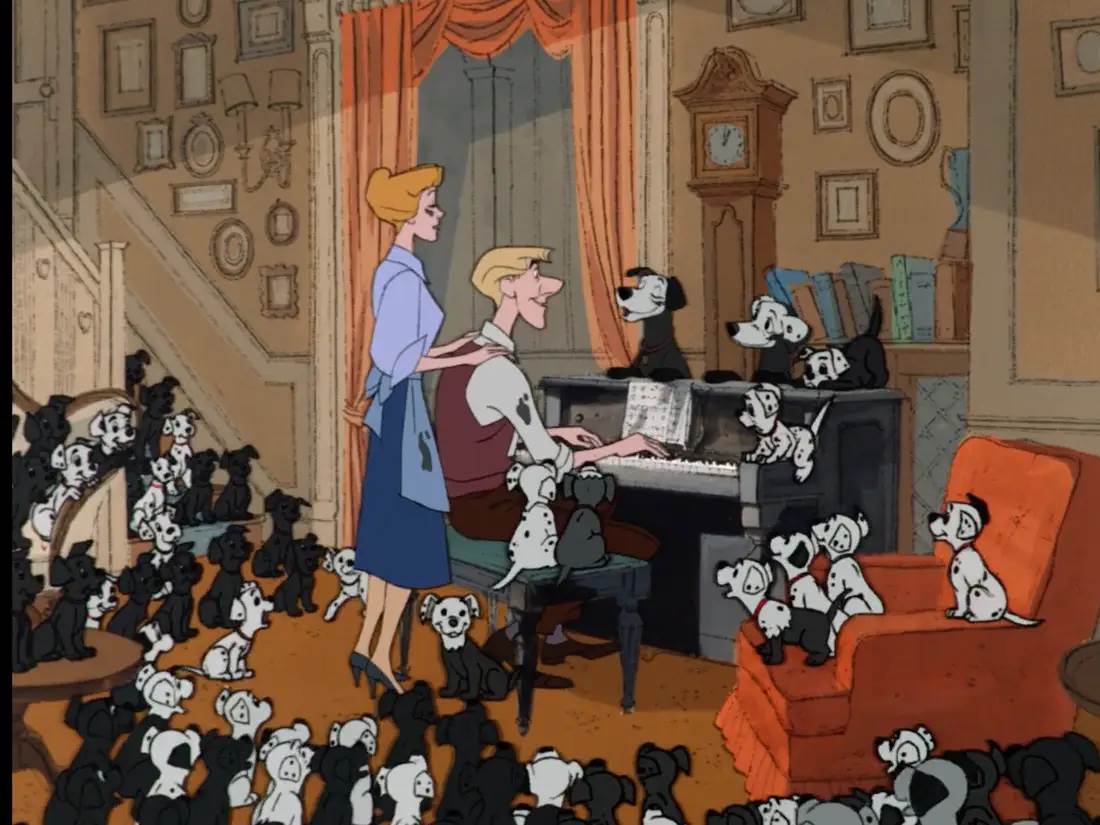

Do you like Frozen? How many times have you sang “Let it Go” in the privacy of your car? What about Zootopia? Remember when you saw Nick getting bullied as a kid and teared up? Or maybe a little further back, When you saw Simba talking to his father in the clouds above the grasslands in The Lion King, or privately sang “Part of Your World” from The Little Mermaid in your car too. My point is, without one particular film from the Walt Disney Animation Studios, you wouldn’t have any of those other greats. But which movie? For that we travel back 60 years to the day, to London, where we saw two dogs, their 15 puppies, 84 additional puppies, and their songwriting humans in the classic film, 101 Dalmatians.

To catch you up, 101 Dalmatians, the 17th film from Walt Disney Animation Studios, then Walt Disney Productions, debuted in theaters on January 25th, 1961. In it, we see dalmatians Pongo and Perdita and their humans Roger and Anita, in a delightful meet-cute where both couples meet and fall in love. Later, Perdita is due to give birth to puppies, but Anita’s boss, Cruella De Vil, wants them for a new fabulous spotted fur coat. Cruella’s henchmen Horace and Jasper kidnap the puppies, and Pongo and Perdita initiate the Twilight Bark and dogs and cats across the country are now on the lookout for their children. Spoiler alert: The original 15 puppies, as well as 84 others, are found and saved after hijinks and adventures in the countryside, making it home safely, now totalling 101 Dalmatians. Hey, that’s the title! But how did this film change animation and save feature production at the studio? For that, let’s go back a little further.

After coming out of World War II, stepping away from the “package features” of Make Mine Music and Fun & Fancy Free and the like, leaning more towards Peter Pan and Alice In Wonderland, Walt Disney once again found success with the fairy tale, Cinderella. His two greatest hits (financially) were princess fairy tales, with both Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Cinderella. Even though distracted by television and a new theme park in the 50’s, Walt took on the elaborate endeavor that was Sleeping Beauty. Inspired by the work of Mary Blair, though her art doesn’t really give well to actual animation, Walt enlisted Eyvind Earle as the lead artist on the project to give a very detailed and gothic beauty to the film. The film was an elaborate and expensive work of art, with the production lasting six years with some sequences taking all six years to produce. Some backgrounds on the film were so detailed and beautiful that artists worked on a surface the size of bed sheets. Certain of a sure thing at the box office, more money and time was poured into the film. The last two worked, right? Certainly this one would not fail. But it did. Now, it didn’t fail at the box office per se, as it’s numbers were high. However, the production costs grew so large that there was no way the box office would recoup the cost to produce, and the film was only considered to be a moneymaker upon later re-releases. Reportedly, Roy Disney confronted Walt about the astronomical costs of producing animated features, and suggested he shut down feature animation and focus on television.

The animation process back then was a lot more intricate than it is today, especially because hand-drawn animation in this traditional format, bluntly, is dead. It was time consuming, labor intensive, and most importantly for our story, it was expensive. Animators would take pencil to paper and draw detailed pictures one by one creating the illusion of movement. 24 drawings make up one second of film in the final movie. At this time, each of these drawings are then handed off to be “inked.” A different artist will then take that drawing, lay a clear acetate “cel” over it, and trace over the drawing in ink. Thus eliminating errant pencil lines and strokes, giving a clean look to the final product before being handed off again to the paint department where different artists fill in the inked lines with color. Again (and I can’t stress this enough), this is done for each frame. One by one. Animators do the drawing, inkers do the ink, painters fill it in. One by one. 24 of these make one single second of film. Sleeping Beauty is one hour and sixteen minutes long. That is 76 minutes. 4,560 seconds. That is almost 110,000 drawings that were retraced in the inking process almost 110,000 times making the final cels in the film. A full look at how the animation process works (from a promotional film for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs) can be seen below. This was largely the process up to 101 Dalmatians.

Courtesy Steve Little

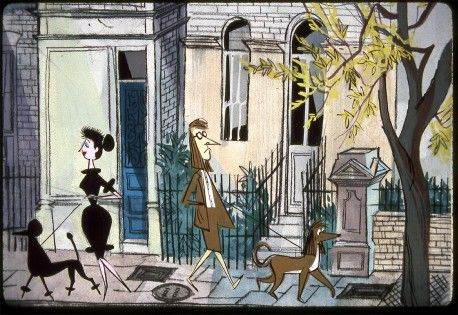

101 Dalmatians is decidedly different from any other animated production from the studio at that time. It wasn’t a fairy tale, it wasn’t a vintage well-known story being told. It was a modern story, set in the present time (that the film was released). There are no singing animals, there is no mysticism or witches, there were even scenes where dogs are watching television. It was different. The production design carried over a bold, modern look, with hard angles and lines. Confronted with the financial restraints of the impact from Sleeping Beauty before it, the studio had to cut costs however they could, they just needed to find the answer.

Ub Iwerks, animator and technical filmmaker, was playing with a new technology that was emerging for businesses but felt he could use it in filmmaking and animation as well. According to legendary animator Floyd Norman, “They had been playing around with it and they were getting it to work, but never on a feature film. We had a new film with a bold graphic look, a new production design that was totally different from what we had been doing with the European fairy tales. So all of these elements came together. So we said – we’ve got the right story, the right process, and the fact that it fits the film’s production design. It was just perfect.”

101 Dalmatians Concept Art

Thanks to Iwerks, 101 Dalmatians was the first film to use a xerography (or “Xerox”) process. When I say Xerox, you probably immediately think of a photocopy. “Oh so they photocopied all the dogs! That’s why there’s so many! That’s how they cut the costs!” which is right, but not quite.

The process uses a modified Xerox camera, able to transfer the original drawings from the animators directly onto the cels. Using this process, there was no longer a need for the ink department, those artists who would painstakingly trace over the lines on each individual cel. Whatever the animator drew would end up directly on the cel. Another legendary animator, Chuck Jones, more known for his work on Looney Tunes and with Warner Bros said, “I would say it helped Disney tremendously. They were able to bring in 101 Dalmatians for about half of what it would have cost if they'd had to animate all those dogs and all those spots. Of course, only the Disney studio would think of doing a hundred and one spotted dogs. We have trouble doing one spotted dog.”

Norman called the process “grungy,” adding, “there’s this powder and the acetate is magnetized, and that powder is drawn to the lines. Since that line is made up of a powder, there are going to be a few straggly, powdery things that are going to look messy and not quite as clean as an inker. But now working with this photocopy process, it was a little messy, but what made it work was that it fit [101 Dalmatians’] design sensibilities.”

While the process helped with the cels, eliminating the inking process, it was also used to take previously animated cycles and repeat them. Jones added, “they had a hundred and one dogs, and in a couple of shots there were acres and acres of puppies. There the Xerox helped them tremendously, because they animated eight or nine cycles of action, of dogs running in different ways, then made them larger or smaller, using Xerox, knowing that if there are a hundred and one dogs, and if there are eight or nine distinct cycles, and they're placed at random in this rabble of dogs, no one will know that they all haven't been animated individually.” Similar tricks to this are still in play, even today with computer technology. For example, in Pixar’s Wall-E there are only 8 different trash cubes. Different angles and lighting and color schemes make those 8 cubes look like hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of different trash cubes that appear in the film.

The xerox process wasn’t without its drawbacks. Animators, previously used to handing off their work for final polishing, were now having to refine their own work, and would still maintain the pencil sketch look, with stray lines and errant marks throughout. The xerox camera would copy these marks and lines to the cel, losing the refinement and blend of the inking process. Though, animators kind of liked that. “For the first time ever the animators were seeing their pencil lines appear on the screen. And they loved that; they thought that was just great,” said Norman. This is far more noticeable in the present day, thanks to high-definition blu-rays and digital transfers. Viewers can now see the imperfections with ease, which can either perturb or delight depending on the person watching. Reportedly, the advent of the Xerox process also led to the closure of departments at the studio, namely the Inking department, and cut the number of artists at the studio from over 550 down to 75.

This xerox process was so successful (depending on how you look at it) that it was used for every film from 101 Dalmatians up through Oliver and Company, even being used on classics like Mary Poppins and Who Framed Roger Rabbit. Reportedly, Walt Disney himself was not fond of the process, as he believed that it gave the films a cheaper, rougher look, especially when compared to his earlier films like Fantasia and Pinocchio, and even the aforementioned Sleeping Beauty which was released right before it. You don’t have to be an animation student or historian to recognize that there are vastly different looks in the different eras of films from the studio. 101 Dalmatians does not look like Pinocchio, and Bambi does not look like Alice In Wonderland, and Mulan does not look like The Rescuers. One can argue it was the differences in the artists, the advances in technology, or even just who directed it. All of which are valid arguments, but when a technology comes in to play that helps even the poorest performers at the box office break even, it’s obvious that that technology will stick around until something even better comes into play.

CAPS

Enter the Computer Animation Production System, or CAPS. I could write a whole other Laughing Place article about CAPS, but (I’m sure) that will be another day. Quickly speaking, The CAPS system gave Disney Animators a slew of new tools, including the digital replacement of the multiplane camera (also a technique previously left behind in favor of cost), transparent shading, and the blending of colors in an essentially unlimited digital environment. For our story needs today however, CAPS killed the Xerox process. Disney worked with an emerging computer company that was part of Lucasfilm in the 80s, Pixar, to develop the system. One of the features of the proprietary software was the ability to scan drawings into the computer and eliminate the need for cels altogether, digitally painting the backgrounds and shading using that aforementioned unlimited palette that the artists now have. Though The Little Mermaid is credited as the first film to use the CAPS system, that was only sparsely. It was The Rescuers Down Under that was fully created using the CAPS system (also making it the first digital movie ever), an ironic twist since The Rescuers was made using the Xerox system, and it’s sequel is arguably more beautiful, more artistic, and more influential than the original.

Even though it was suggested Walt shut down animation, he persisted. He did keep the xerox system, saving the artform at his studio simply because it was cheaper and Roy seemed to approve. Walt Disney passed away in 1966, with later films that used the system going on without him. While financially 101 Dalmatians may have saved feature animation at the studio, it’s the storytelling that made it the tenth highest grossing film of 1961 and keeps it widely regarded as Disney’s best film of the ’60s. Numerous re-releases over the years, performing well each time have also kept the story alive. Further proof that no matter what you do “on the cheap” doesn’t matter as long as the entertainment being offered is of quality. A recurring lesson that would later be forgotten at the same studio that 101 Dalmatians saved.