“Talking Shop” with Guillermo Del Toro And Glen Keane Regarding “Over The Moon”

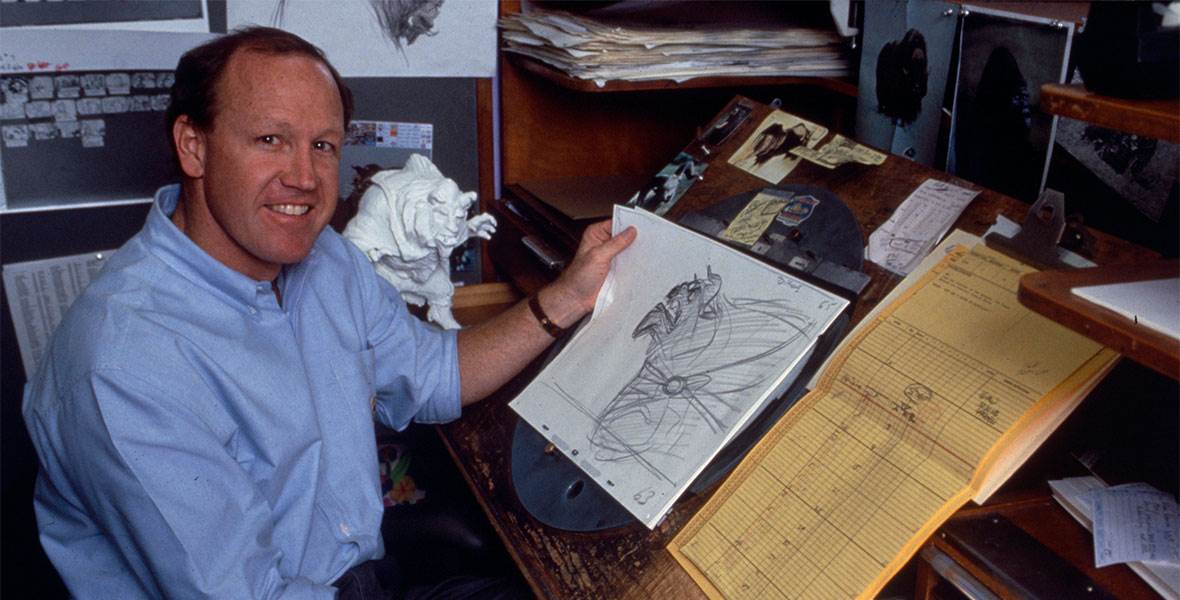

Yesterday, Netflix held a Virtual Q&A with the director of their animated feature, Over the Moon, Glen Keane. Keane has long been a staple in animation, contributing to many films of the Disney Renaissance and the classic characters of the era, and was even named a Disney Legend in 2013 thanks to his work on Ariel, The Beast, Tarzan, Pocahontas, Rapunzel, and others. He left the company in 2012, reportedly saying in a resignation letter, “I am convinced that animation really is the ultimate art form of our time with endless new territories to explore. I can't resist it's siren call to step out and discover them."

The origin story of Tangled, back when it was known as “Rapunzel Unbraided” saw Keane in a director’s chair for a while before leaving due to a combination of health issues and story troubles. According to Insider, when asked if one of the reasons he left Disney was because he didn’t get the opportunity to direct, Keane replied, "I started to develop another project there that I love, and I think that that was going to be...I really was happy at Disney and loved my relationship there, but there's something about a huge studio that you carry so much weight on your shoulders as what that film has to represent. [There are] so many interests in a big company and I experienced that very much with 'Rapunzel,' how many different focuses of management and interest were in the changes of that story." He left the company, telling then-president of Disney Animation Ed Catmull, “I want to live creatively without walls.”

After leaving Walt Disney Animation Studios, he created a hand-drawn short for Google, the first made at 60 Frames per second, Duet. He did a short for the Paris Opera, Nephtali, and collaborated with Kobe Bryant for the Oscar-winning Dear Basketball. After all that, Over The Moon is his true directorial debut for a feature-length film.

The Netflix Q&A, moderated by Oscar-Winner Guillermo Del Toro, was less of a Q&A and more of these two just “talking shop” about the animation in Over the Moon.

Over the Moon follows young Fei Fei, whose mother told her about the legend of the moon goddess Chang'e, who is forever trapped on the moon waiting to be reunited with her true love. Fei Fei’s dad tries to tell her the scientific explanation but she sticks with her mom’s. After the passing of her mother, years later, Fei Fei comes home to find his father cooking with another woman (and her son). To prove that he shouldn’t move on, and that her mother is waiting for him much like the moon goddess, science prodigy Fei Fei sets out to build a rocket to the moon to prove that Chang’e is real.

First and foremost, Del Toro addressed Keane, who is widely known for his work on the traditionally hand-drawn films of the Disney Renaissance, on why he chose 3D Computer Animation over the 2D format. The answer was simple. Lighting. The different environments of Earth and the Moon needed complex lighting designs because of the translucency needed for the moon, as well as the realism of Earth. It was the topic of translucency that got Guillermo very excited to talk about the food seen in the Moon Cake baking sequence. Near the beginning of the film, we are performed a musical ditty about the baking of moon cakes, while also seeing the condition of the mother’s health deteriorate, wherein there are plenty of beautifully animated food items, including eggs, and powdered sugar, animated to perfection with exquisite detail.

The lighting effect on colors also played a big part in the film. Keane recalled a research trip to China where he was commenting on what he felt were a surprising amount of bare white walls. Someone else on the crew pointed out that they weren’t white, there are “at least 8 different colors there” pointing out the way the walls reflected the colors of the things surrounding it. Using that as inspiration, the made the choice that Earth would mostly be composed of reflected light patterns, while the environments on Lunaria (The world on the Moon) would be comprised of source light.

Aside from lighting and coloring the animation in the film is absolutely beautiful. From the gestures and emotions of silent characters, like the rabbit Bungee, to subtleties in the human faces. One exemplary scene was pointed out by Guillermo, where Fei Fei meets Dad’s new girlfriend Mrs. Zhong. Anybody who knows the feeling of seeing this from the child’s perspective could relate, and that feeling was conveyed all too well with little dialogue and emotions told entirely by the facial animation of Fei Fei. Guillermo points out how brilliant the animation is, especially in the corners of the mouth, noting how he himself has had trouble achieving that without venturing into The Uncanny Valley.

Glen appreciated that Guillermo recognized this, saying that if you could peel back the character and look at all the rigging, you’d “find the engine of a Lamborghini” with so many additional pieces just to pull that off.

Guillermo and Glen discussed that all the rigging in the world doesn’t matter without the right performance. Back in the day, animators would be referred to as “actors with pencils,” and though the instrument of choice might be different, the philosophy is true. Coming from the Disney background where the vocal talent is filmed and the animators use that as reference for nuance, someone on Glen’s team said “we’re not doing that.” When asked why, the response was because they wanted the animators to use their own life experiences to convey the emotion the characters would display in the film, not the vocal talent in a recording booth. Glen loved the idea. Guillermo added that a similar philosophy is being added to the stop-motion techniques in use on the upcoming Pinocchio, and told Glen that whatever they learned on Tangled, as brilliant as it was in terms of performance, they took it to the next level with Over the Moon.

Fei Fei does eventually encounter the moon goddess, Chang’e. But it’s not what she expects. Almost like an international pop-star, Chang’e (voiced by Hamilton’s Phillipa Soo) takes the stage with a rousing number. Picked up by Guillermo, much to Glen’s delight, there was a reason for this. A goddess would be represented with softness, and even gentle movements, almost like a traditional fairy tale representation. They made Chang’e harsh, “an urbanite,” to give subtle reference that Fei Fei’s mother was the true goddess. Of course, by the end of the film we do see a softer side of Chang’e, one that represents those traits as well, albeit briefly. Don’t be confused though, Chang’e is not a villain. There are no villains in this story, aside from the unnamed villain, the concept of loss. As Glen put it, “Nobody can stop that moving train.” A story the crew know all too well, as the screenwriter, Audrey Wells, passed away from cancer while working on the film. Tones that Glen said can be seen in the film with scenes like the “Chamber of Exquisite Sadness” which can only come from a place that someone dealing with something like that can grasp. The movie was also written as a gift from Wells to her daughter, knowing what would be occurring in the future. Wells never got to see the final film.

One thing that Glen brought up with Guillermo is how important a character’s hair is to him. Dating back to Ariel in The Little Mermaid, and even to an extent Ratigan in The Great Mouse Detective, Glen has always seen the character’s hair as a symbol of their struggle. Ariel’s hair would float aimlessly en masse under the water, where she wanted to leave. Beast’s fur, covering his body, would be his curse until he was human again. In the case of Over The Moon, we see Fei Fei with a clearly homemade cut after her mom passes away, and only later in the Chamber of Exquisite Sadness do we actually see a flashback of her hacking away at the hair remembering how her mom used to run her hands through, and play with it.

After Fei Fei's mother dies, she sits on the dock where they'd spent so much time together and wonders aloud what she should do to get her dad to postpone his upcoming marriage. She believes that her father should wait to be reunited with his late wife, as in the legend of Chang'e and Houyi. Fei Fei looks to the moon and sees a crane flying directly at it, prompting a musical number, and her eventual trip to the moon. Once Fei Fei returns home, she once again encounters the crane on the dock. After sharing a few seconds of eye contact, the crane takes off close to Fei Fei's head, grazing her hair with its wings. Guillermo asked Glen the question much of the audience was thinking, especially those familiar with the Chinese cultures and traditions. Is the crane Fei Fei’s mom? No definite answer was given. He even went on to say that the scene had dialogue in it, “when I first storyboarded that, Fei Fei was talking to her mom. And then we took all of that dialogue out and it played so much better. And her mother makes our appearance there, in that crane in a sense."

While not as ambiguous as the crane perhaps (or maybe more!), based on the conversation with the two directors, The Wizard of Oz has a heavy influence on the film. Even Chang’e has elements based on the Wizard at first, appearing behind a giant curtain. But the real question, did Fei Fei actually go to the moon? While all parts of the movie point to “yes,” Both Guillermo and Glen point out that there are several clues peppered throughout that maybe she didn’t. One thing for sure is that Glen said they didn’t want to do the “it’s all a dream” that was done in The Wizard of Oz, but rather leave it up to the viewer if she went, yes or no. Did she go to the moon? Find out for yourself, Over the Moon is streaming now on Netflix.