The New Nine Old Artists: The Original Nine Old Men

You can’t do much in the realm of animation without inevitably hearing about Walt Disney’s original “Nine Old Men.”

A term reportedly borrowed in jest by Walt himself after it was given by Franklin D. Roosevelt to nine out of touch Supreme Court Justices in the mid 30’s.

Though (at the time) not old or “out of touch,” the nine animators under Walt’s employ all but created and mastered the artform. Together, they innovated new ways to tell stories using animation. They had already stood on the self-taught shoulders of artists like Ub Iwerks and Art Babbitt, but also brought in an education from some of the greatest art schools in the country.

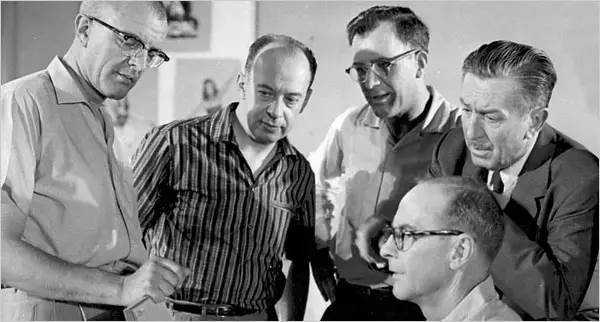

Calling Eric Larson, Frank Thomas,John Lounsberry, Les Clark, Marc Davis, Milt Kahl, Ollie Johnston, Ward Kimball, and Wolfgang “Woolie” Reitherman the “Nine Old Men” does kind of imply that they worked together all the time, always. However, that was not the case. They were still individual artists with their own styles, aesthetic, and approaches as unique as their own signatures. Walt would also use them as he saw fit based on the project. Marc Davis, for example, was heavily involved with the production of Bambi and as such had no or little involvement in Fantasia. Eventually, some would stay working on the animated films while others would go work on Disneyland.

Have you ever seen Ocean’s Eleven? That movie where a ragtag group of thieves attempt to pull off a major heist at Las Vegas casinos? Remember, how even in this collective group, there are still subgroups almost, of closer friends and even pairings that might not necessarily get along? While the movie I’m referring to is fictional, it still grasps this group dynamic quite well. The Nine Old Men also had these situations. Usually you won’t hear of Frank Thomas mentioned without also hearing the name Ollie Johnston, as the two often worked together and were great friends. Less publicized but still a great duo were Marc Davis and Milt Kahl, who were inseparable though quite the opposite. Davis would carry a sketchbook wherever he went while Kahl would drop his pencils and revert to a chess board or fishing pole as soon as the work day was done.

Keeping with the Ocean’s Eleven analogy, throughout the trilogy yes, we focus on those 11 guys, but they also have a slew of supporting allies who help them achieve their thievery goals. In this instance, this would be the inkers and painters, the story artists, and the hundreds if not thousands of artists whose names we might not have heard time and time again who passed through the hallowed halls of the original studio. Collectively, they turned the Walt Disney studio into the icon it became. Churning out masterpiece after masterpiece like Fantasia, Dumbo, Bambi, Cinderella, Peter Pan, and Alice in Wonderland.

To ensure the legacy of the art of animation, it was realized that there would be a new generation of animators and artists behind this group. At a point in the 30’s Walt Disney had sent several of his animators to study at the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles. He wanted the artists to be classically trained and built a relationship with the institution. When he discovered that the school was having some financial difficulties, he kept it afloat. The Chouinard Art Institute and the relationship with Walt, as well as it’s part in a possible “City of the Arts,” (think of an earlier EPCOT style project) could be the subject of a whole other story (perhaps another time) but the end result became a single school incorporating the Chouinard Institute as well as the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music. That school was the California Institute of the Arts, or “CalArts.”

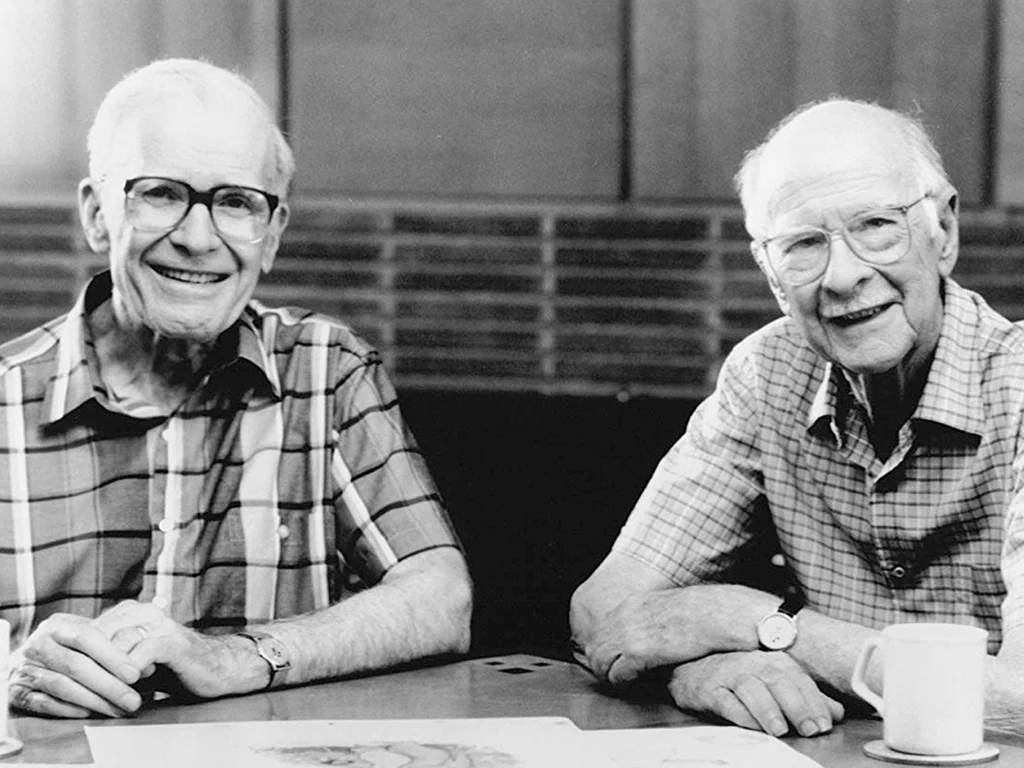

CalArts, another familiar name to animation fans, opened their doors several years after Walt’s death in 1970, and it gave rise to a legendary class of animators (some of which you may read more about in this series) from the innovative character animation program that was at the school. Students were taught by Walt’s artists at the school, and many would get jobs at the Walt Disney Studio where they worked under the mentorship of the veteran animators, notably Eric Larson. Some of the new generation, like Brad Bird (The Iron Giant, The Incredibles), were able to work with some of the more elusive of the nine, including Milt Kahl.

Just as Walt’s Nine Old Men were a second generation of artists at the studio who helped innovate and develop the craft, they went on to inspire and in some cases, literally teach a new generation of animators after them. Together, they collaborated on a series of feature films where they honed their craft and perfected their skills and pushed the artform even further, leading into an era that came to be known as the Disney Renaissance. While this span began in the 80s and ran into the 90s, it’s hard to believe that that time period itself was over 30 years ago. Now another generation of animators and artists have a generation to look up to and credit as their inspiration or role models.

The title of the Nine Old Men has always and will always refer to those artists in that collective, but someone recently asked me who would have that title now. Who are the masters that students and animators today look at as the pinnacle of the form? Some names came to mind immediately and without a second thought. Others took a bit of time to refamiliarize myself with their work, as it may not have been popularized in DVD bonus features or as heavily marketed by the Walt Disney Company as others. I’m treating this series as a sort of nomination list as to who I’d pick should there be a new title of some kind recognizing this particular generation of inspirational artists and I was asked for my opinion.

Next time, we’ll launch into the real meat of the series and take a look at an admittedly easy first choice if you’re familiar with the art of animation, and take a look at an artist who always seems to oversee and animate characters who have troubles with hair….