“Inspiring Walt Disney: The Animation of French Decorative Arts” Takes Over Edition of “Sundays At The Met”

Earlier today, the Metropolitan Museum of Art held a special panel in their Sundays at the Met series that tied in with their current exhibit that is coming to a close soon, Inspiring Walt Disney: The Animation of French Decorative Arts.

In the session, a panel of experts, including two Disney animation legends, reflect on their careers, the making of the classic animated film Beauty and the Beast (1991), and the lasting legacy and impact of Disney on American culture. Glen Keane, Animation Director, Glen Keane Productions and Supervising Animator of The Beast in the film, along with Don Hahn, Producer and Director, Walt Disney Animation Studios and Carmenita D. Higginbotham, Dean, Virginia Commonwealth University School of the Arts join moderator Wolf Burchard, Associate Curator, European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, The Met to discuss the film and it’s 18th century influences.

For those who couldn’t make the in-person panel, the MET also streamed it live on their YouTube and Facebook pages.

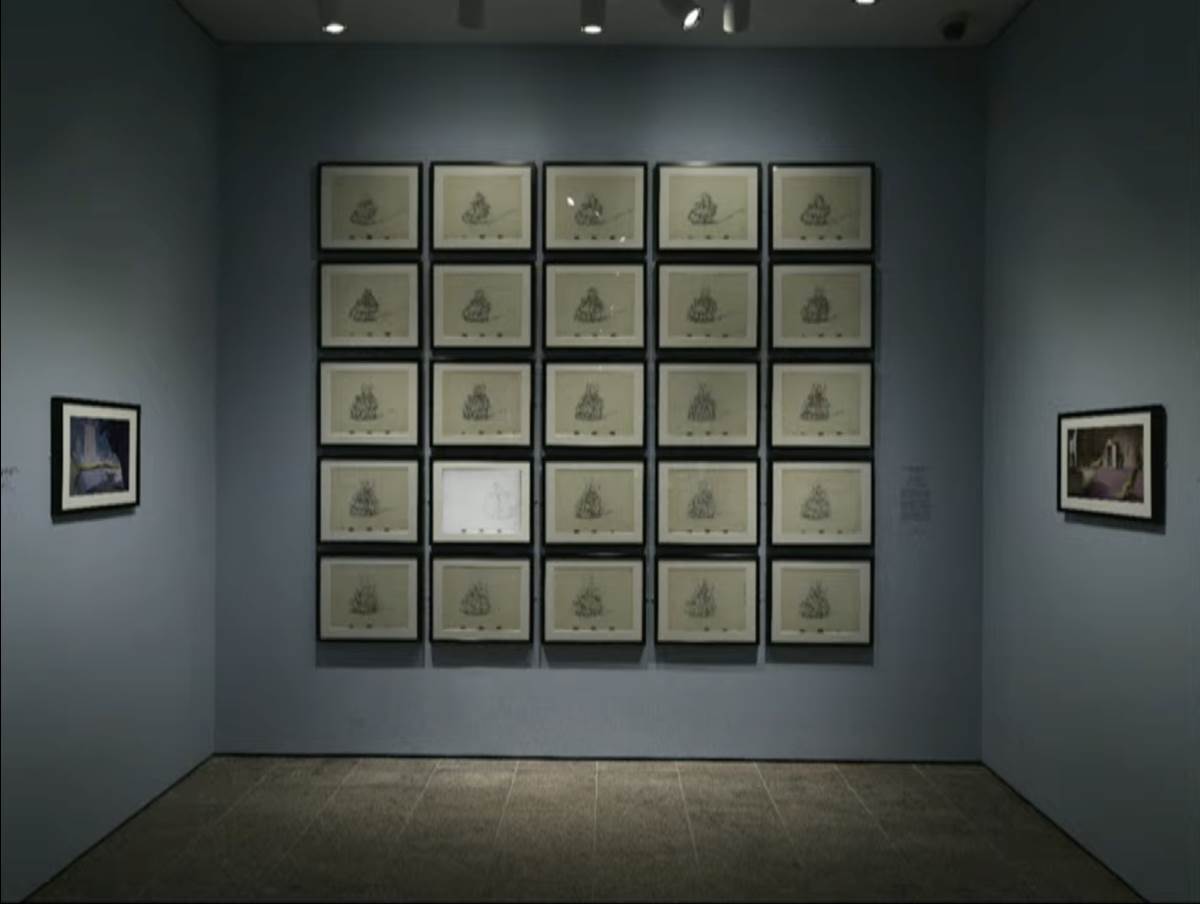

The panel focuses primarily on the 1991 Walt Disney Animation Studios film, Beauty and the Beast and some of the behind the scenes history regarding its production. Briefly at the beginning of the presentation, host and moderator Wolf Burchard shares the influences of 18th century European art, specifically the Rococo period and furniture designs including a familiar looking candelabra. Burchard also shares his appreciation for the laborious process of the art of animation, and even showcases a specific wall in the exhibit that features 24 individual drawings from the dress transformation sequence from Cinderella, representing the draftsmanship that goes into these productions for only a single second of film.

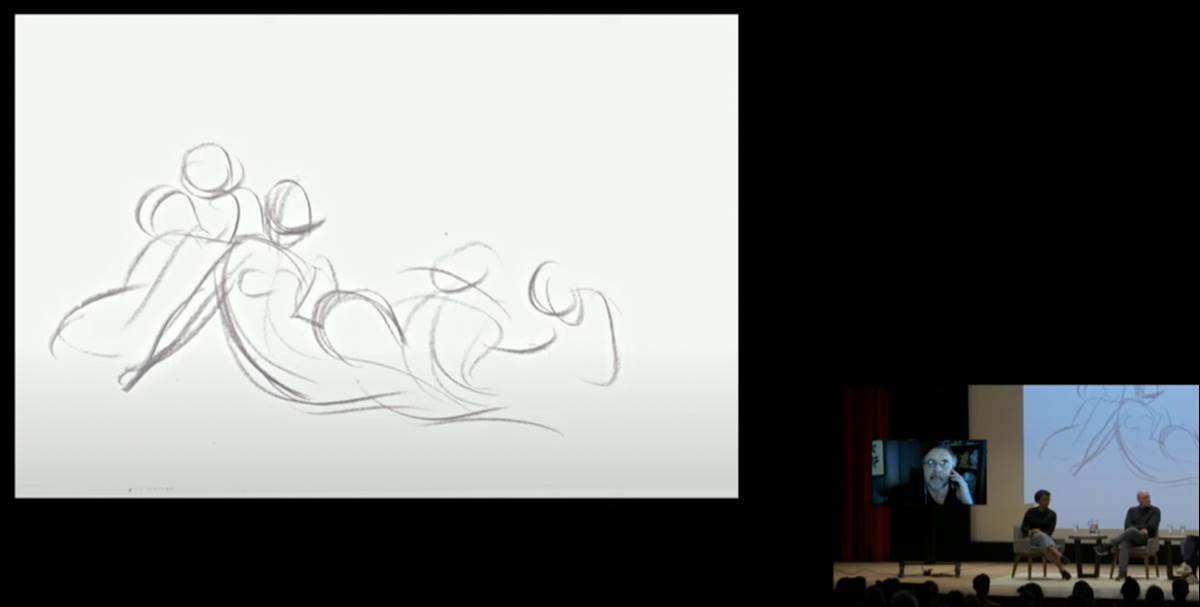

Once Glen Keane and Don Hahn take the stage alongside Burchard and Higginbotham, the talk turns to the production of the film, touching upon production hiccups like the (now more commonplace) story about the far more humanized, less-magic and enchanted furniture original version of the film. Those who aren’t too familiar with the production of the film will delight in these tales, but anybody with any DVD or Blu-Ray copies of the film will recognize most of this content from the bonus features on their discs. We also didn’t get much input from producer Don Hahn as his audio was disconnected for his virtual appearance during most of the panel discussion. The focus was then on Glen Keane and his iconic animated sequence of the transformation of the Beast. The story goes that he only had a week to do it based on the official production schedule, but Hahn knew how important that scene would be and allowed him to take the time he needed to get it done. In fact, the story has been told numerous times before and be found in the video below in a more succinct fashion, sharing the influence that master artists before him had on his work.

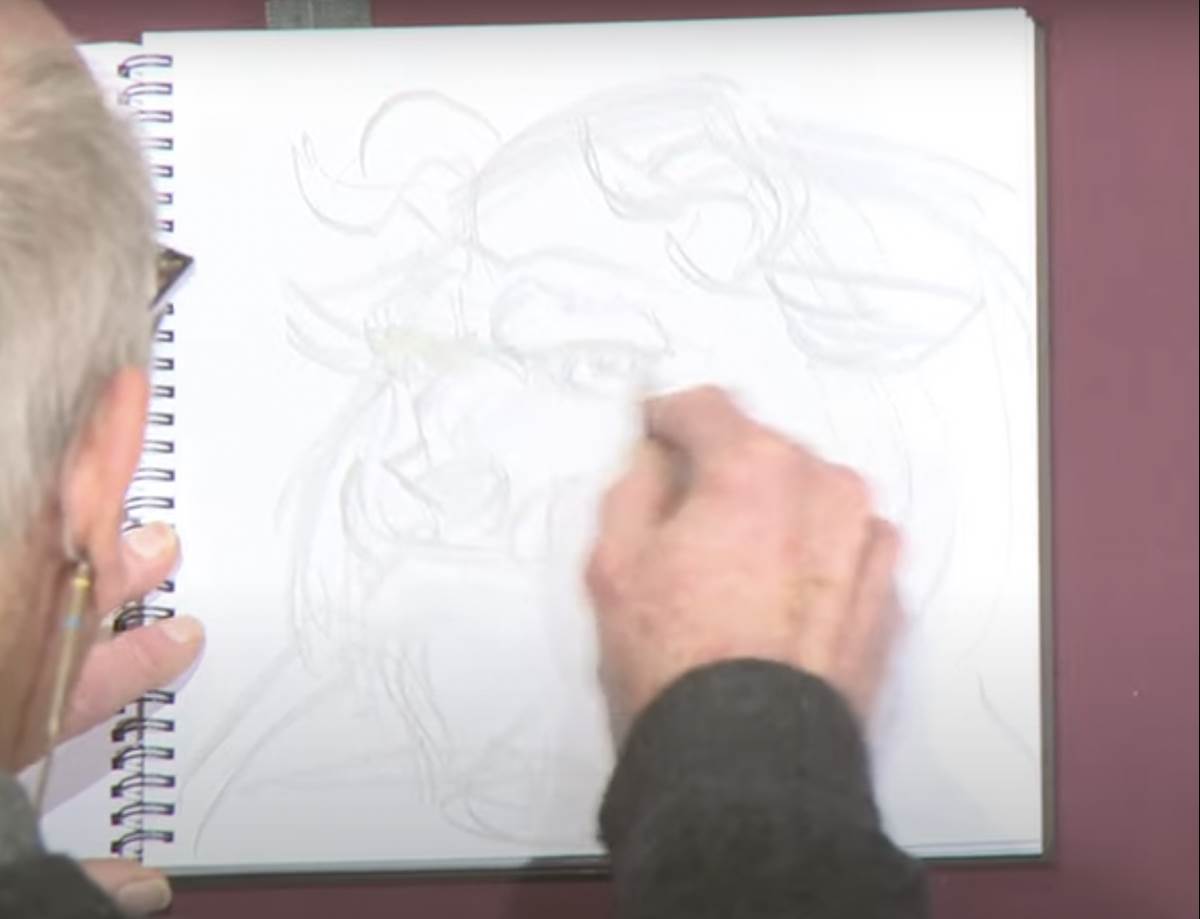

The Sunday at the MET feature also showcases Keane taking to a sketchpad and sharing the inspiration of the Beast character, and its roots in a taxidermy buffalo head purchased by Hahn, who then tried to include it in an expense report. The session ends at this point, but we are reminded that there are only a few more days left to enjoy the exhibit at the MET.

From the official MET website:

Pink castles, talking sofas, and objects coming to life: what sounds like fantasies from the pioneering animation of Walt Disney Animation Studios were in fact the figments of the colorful salons of Rococo Paris. The Met’s first-ever exhibition exploring the work of Walt Disney and the hand-drawn animation of Walt Disney Animation Studios will examine Disney’s personal fascination with European art and the use of French motifs in his films and theme parks, drawing new parallels between the studios’ magical creations and their artistic models.

Sixty works of 18th-century European decorative arts and design—from tapestries and furniture to Boulle clocks and Sèvres porcelain—will be featured alongside 150 production artworks and works on paper from the Walt Disney Animation Research Library, Walt Disney Archives, Walt Disney Imagineering Collection, and The Walt Disney Family Museum. Selected film footage illustrating the extraordinary technological and artistic developments of the studio during Disney’s lifetime and beyond will also be shown.

The exhibition will highlight references to European visual culture in Disney animated films, including nods to Gothic Revival architecture in Cinderella (1950), medieval influences on Sleeping Beauty (1959), and Rococo-inspired objects brought to life in Beauty and the Beast (1991). The exhibition also marks the 30th anniversary of the animated theatrical release of Beauty and the Beast.

Regarding the exhibition and Beauty and the Beast, a series of galleries has been devoted to the 199 film, which Walt Disney himself had suggested for animation in the 1940s and 1950s. The famous tale was first published in 1740 by Suzanne-Gabrielle Barbot de Villeneuve, although a later, abridged adaptation (1756) by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont is more widely known.

This expansive section explores topics of anthropomorphism and zoomorphism in 18th-century French literature and decorative arts, Disney’s satirical take on Rococo fashion, the interiors of the movie’s enchanted castle, and the design and animation of the Beast and other characters. On view is a touching, 16th-century portrait lent by Ambras Castle in Innsbruck, Austria, of Magdalena González, which has been associated with the story of Beauty and the Beast for generations.

Young Magdalena was afflicted with a genetic condition causing the entirety of her body to be covered in unusual amounts of hair; her and her family’s story was one of alienation and oppression. Preparatory movie sketches shown alongside 18th-century clocks, candlesticks, and teapots (evoking the characters of Cogsworth, Lumiere, and Mrs. Potts from the movie) will illustrate the ways in which both Disney animators and Rococo craftspeople sought to breathe life into what is essentially inanimate. Highlights also include a clock on pedestal by André Charles Boulle, gilt-bronze candlesticks by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier, and early Meissen teapots, including an anthropomorphic one of a bearded man riding a miniature dolphin, as well as a pair of Sèvres elephant vases designed by Jean-Claude Chambellan Duplessis.

Particular focus is given to the aforementioned Beast’s transformation scene, inspired by sculptor Auguste Rodin’s The Burghers of Calais, as well as the ballroom scene, whose vast architectural backdrop drew on the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles.

Inspiring Walt Disney: The Animation of French Decorative Arts is on view now at The Met and is scheduled to run through March 6th, 2022. You can take a look at more of the exhibit during our experience here.