SIGGRAPH 2023: Looking Back At 100 Of Years of Technology Advancements at Walt Disney Animation Studios

As part of Walt Disney Animation Studios’ appearance at SIGGRAPH 2023 in Los Angeles, award winning veteran effects animator and visual effects supervisor Marlon West came over the hill from Burbank to share 100 years of art and technology at the animation studio.

West, who came to Disney after working on Rover Dangerfield and Bebe’s Kids, got his spot in the trainee program, studying effects animation from classics like Pinocchio before being tasked with animating shadows in The Lion King.

While he joked yet lamented the fact that nobody really saw Rover Dangerfield or Bebe’s Kids, he can rest assured - people saw The Lion King. From there, he has contributed to a slew of features from the studio, and with The Lion King being the 32nd entry in the film catalog, and we are on approach to the 62nd with Wish, West has been present for half of the full-length features from the studio. So if there is anyone well versed enough to talk about technological advancements in the world of Disney Animation, it’s definitely Marlon West.

While he is classically trained in the realm of 2D animation, he himself advanced technologically, making the jump from hand-drawn to computer animation after a viewing of the original teaser trailer for The Incredibles. He recalled, telling the audience, that there were people in Disney Animation at the time who essentially said that as long as there are people who want romantic stories, a la The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Pocahontas, et al, there would be a place for Disney Animation. Then he sees this trailer from Pixar Animation Studios:

West commented that the story looked so appealing, so relatable, he knew “the jig was up" and decided to gain a new skill set, jumping over to the computer and learning software like Maya and Houdini. While this took place in a very specific time frame in the history of the medium, West took us back to the beginning of tech advances at the Walt Disney Animation Studios. While West didn’t go into full details on a lot of these entries, he did highlight each of these achievements and I have taken the liberty to elaborate on what made them milestones.

1928 - Synchronized Sound - Steamboat Willie

Not only did Steamboat Willie give us Mickey Mouse, it was the advent of a cartoon short with synchronized sound that really drove in the crowds - allowing them to fall in love with Mickey Mouse of course.

1933 - Technicolor - Flowers & Trees

With new advents in the film industry, the pictures didn’t have to be as monochromatic anymore, and the studio embraced this, releasing the Silly Symphony short, Flowers & Trees in vivid technicolor.

1937 - Multiplane Camera - The Old Mill

One of the most popular and important inventions from the early days at the studio, the multiplane camera allowed multiple layers of glass to be placed with the camera above, vertically, filming down through the panes to add layers of depth to the scene, giving it a rich and realistic look. However, there are only so many panes and cels that can be seen clearly before color adjustments had to be made (approximately 12). A problem that wouldn’t have a solution for about another 50 years.

1938 - Full Length Animated Feature - Snow White & The Seven Dwarfs

Taking everything that Walt Disney and his team learned from making the Silly Symphonies and Mickey Mouse shorts, they combined their efforts into a full-length animated feature, Snow White & The Seven Dwarfs.

1955 - CinemaScope - Lady & The Tramp

Walt Disney made the decision to present Lady & The Tramp in Cinemascope, a widescreen format in which an anamorphic lens “squeezes" the image onto standard Academy format 1:37:1 film. When projecting the film, the anamorphic lens “spreads" the image into a 2:55:1 widescreen image that is nearly twice the standard ratio.

1959 - 70 MM Widescreen - Sleeping Beauty

For Sleeping Beauty, Disney used the Technirama format, which used a larger 70 mm film size, rather than the Cinerama process. Walt Disney’s decision created some hurdles for the studio - backgrounds needed to be widened to fill the wider format. A “standard" format version had to be shot to play in the many theaters across the country that did not have the capability to project the Cinerama widescreen format. Sleeping Beauty also set a new bar for art direction, inspiring many artists who would come to the studio afterward, and influencing films even to this day, including the upcoming 62nd animated feature from the studio, Wish.

1961 - Xerography/Xerox - 101 Dalmatians

Another major milestone reached by the studio was incorporating Xerox technology into the production of animated films. Using this tech, drawings by artists could then be copied directly onto the acetate cels, rather than going to another step in the production pipeline, where artists would paint directly over the drawings onto a cel, cleaning up the lines at the same time as they were being inked. Now, the artists’ lines would be transferred directly (which was great on a feature that required just slightly over 100 dogs). The process was double edged - while the drawings stayed true to what the animator intended, the final product also came with a sketchy look.

You can read more about this process in a previous article celebrating the anniversary of 101 Dalmatians, here.

1985 - First Use of Computer Graphics - The Black Cauldron

While most people will immediately accept the next entry in this list and skip over this one, it must be noted that the much-maligned film, The Black Cauldron marks the first appearance of computer graphics in a production from Walt Disney Animation Studios, with some bubbles and the cauldron being aided by computers.

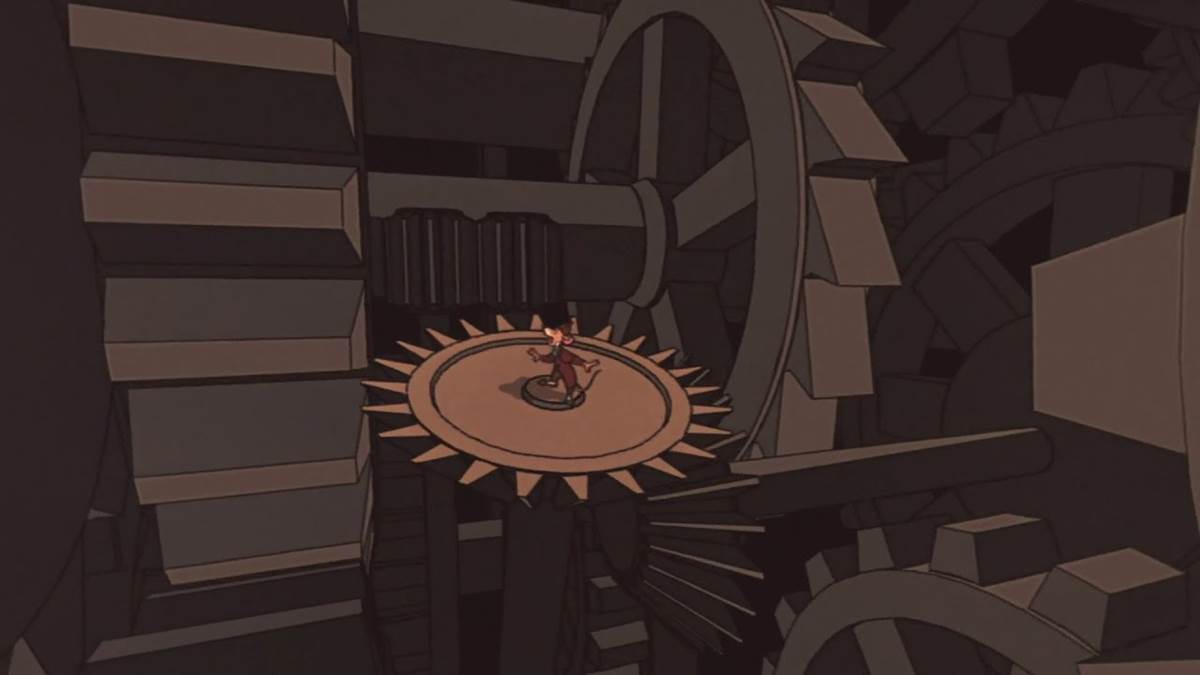

1986 - First Computer Graphics Sequence - The Great Mouse Detective

However, it was The Great Mouse Detective that was a full demonstration of what computers could do in the art of animation. In the climatic scene where Basil and Ratigan face each other within the giant inner workings of Big Ben, all the gears and clockwork are computer generated. But not like you might think, especially in the context of today’s movies. This process occurred so early on, and with the company trying to stay true to its roots of hand-drawing everything, the shots involving the clock’s gears were literally printed frame by frame with the character animation added to them later.

1989 - First Use of CAPS - The Little Mermaid

Then comes a new system that Disney built in collaboration with a little known computer graphics company at the time, Pixar. This system, the Computer Animation Production System (Or CAPS) would aid with digitally painting and compositing the final shots. While some will argue that the first use of the system was in the original opening of The Magical World of Disney, where an animated Mickey Mouse is standing on top of Spaceship Earth at EPCOT, it’s the last sequence of The Little Mermaid, where Ariel and Eric head off with King Triton in the distance that the system was fully used and integrated into a full-length feature.

1990 - First Full Use of CAPS on a Feature - The Rescuers Down Under

With The Rescuers Down Under, it was decided that the studio would go all in on the CAPS system, doing the full feature with the new system. The completed digital cels were composited over scanned background paintings, and camera or pan movements were programmed into a computer exposure sheet simulating the actions of old style animation cameras. Additionally, complex multiplane shots giving a sense of depth were possible. Unlike the analog multiplane camera, the CAPS multiplane cameras were not limited by artwork size. Extensive camera movements never before seen were incorporated into the films. The final version of the sequence was composited and recorded onto film. Since the animation elements existed digitally, it was easy to integrate other types of film and video elements, including three-dimensional computer animation.

1991 - First CG Environments - Beauty and the Beast

For a number of years, it was always kind of hushed that Disney Animation was venturing into the world of computer animation. While other attempts, like the aforementioned clock in The Great Mouse Detective or other shots in Oliver & Company used printed CG imagery to keep the 2D look, Beauty and the Beast went all-in, introducing audiences to fully computer generated environments, and placing the 2D characters within it. Another advance in the CAPS system, which would be used until 2004, when the technology was largely outmoded. Disney wouldn’t reveal how the CAPS system worked until 1994, to keep the idea of the hand-crafted art alive at the studio.

1994 - Computer Generated Crowds - The Lion King

Could you imagine animating, by hand, herds and herds of stampeding wildebeest? It probably wouldn’t be as dramatic as the landmark scene in The Lion King. While the scene itself does end with an emotional gut punch, its visually appealing the whole time thanks to the advent of CG Crowds, capable of generating hundreds of wildebeest that appear in the scene. This marked when Disney first started revealing that they were using the CAPS system to audiences everywhere, showing off the capabilities of the system on the wildebeest scene. CAPS would see its final days in use on production in 2004’s Home on the Range.

1999 - Deep Canvas - Tarzan

In response to an unusually difficult problem (animating 10 minutes of painterly looking, densely lush jungle with a rela-tively small crew), the programming team wrote software to interpret, based on a 3D database, the intended location of each and every brushstroke in a painting, then actually repaint that painting over and over from various camera angles. As the scene progresses, more and more brushstrokes are added to fill in gaps from the previous frames. In this way, artists (with considerable help from a technical director) are able to use their artistic intuition to create entire 3D environments that can intercut seamlessly with the 2D world of the animated film.

Deep Canvas also took what the Multiplane camera did decades earlier and did it digitally, and this time without those pesky color schemes for clarity on acetate animation cels.

2012 - Meander - Paperman and Feast

Meander started development in 2010 as a stand-alone vector/raster hybrid animation system with the primary goal of bringing the power of digital tools to hand-drawn animation. Although originally targeting 2D cleanup animation, it was designed to be general enough for use throughout all departments in the studio.

The primary goal of any artistic tool is to allow an artist to express their intent as quickly and easily as possible– unencumbered by complexity of interface. In the case of drawing, it’s difficult to improve upon pencil and paper. To be compelling, Meander has to empower artists in ways not possible without a computer while not compromising the ease-of-use of paper.

Once we could ensure that the drawing quality was as good or better than all other drawing tools, we could then focus on adding the new abilities that the geometric information would allow. For example, Meander has inbetweening capabilities– given similar drawings on different frames, the system can interpolate the strokes and draw them as if the artist had drawn them. While the system cannot make artistic choices, it can however assist the artist in doing arduous tasks such as inbetweening subtle movements that require great precision.

Taking this concept a step further– on Paperman, the stroke geometry could be “attached" to an underlying 3D animated character. Given 3D animation and strokes drawn on top, those strokes are then “carried" along with the 3D animation but always drawn as two-dimensional strokes. This allowed us to create the effect of an animated painting on Paperman – with all the benefits of CG animation (smoothness, depth, stability) and combine it with the benefits of hand-drawn animation (emotional cues from lines, every frame drawn to camera). This technique was also used in the short-film Feast.

After its use on Paperman and Feast, Meander’s core functionality was repackaged into a platform-independent library called MeanderKit, allowing it to be integrated into a variety of tools on different devices. It is noticeable again in use as what helped bring the hand drawn Mini-Maui come to life in Moana.

2013 - Matterhorn - Frozen

Originally, animated movies were created using traditional hand-drawn animation techniques. Teams of animators would draw all characters and the surroundings frame by frame which would be assembled to compose the final film. However, people can only draw so many things, and things like water, smoke and fire have a level of richness and degrees of freedom to their composition and movement, which makes it nearly impossible to animate “by hand" in any reasonable amount of time. That is where Matterhorn came into play. Using technology and physically-based algorithms, environmental effects like water, smoke and fire are governed by physical equations, so the software allows computers to do all the heavy computation to solve those equations. A proprietary physically based simulator, It was originally developed for creating snow effects in Frozen (2013), proving to be highly efficient at simulating large amounts of snow interacting with characters and the environment around it. Recently Matterhorn has been upgraded with more advanced constitutive models to be able to simulate more materials: mud, foam, sand, etc.

2014 - Hyperion - Big Hero 6

Hyperion is Walt Disney Animation Studios’ in-house renderer and is a physically-based path tracer. A renderer is the software that takes all of the models, animations, textures as well as lights and other scene objects and produces the final image that makes up an animated movie by calculating how the light bounces around a virtual scene and shades the objects. Hyperion handles several million light rays at a time by sorting and bundling them together according to their directions. When the rays are grouped in this way, many of the rays in a bundle hit the same object in the same region of space. This similarity of ray hits then allows the artists and the computer to optimize the calculations for the objects hit.

Thanks to this novel method, the studio can render the entirety of say, San Fransokyo, without resorting to tricks like creating paintings to imitate distant scenery. With this kind of power, the studio can almost literally put the audience on Baymax's shoulders as he rockets through San Fransokyo without any constraints.

2016 - The Water of Moana

One of the hardest things for animators to work on, especially effects animators, is water. And of course, here comes a movie that has the lead character live on an island, and spend most of her story on a journey aboard a raft, surrounded by….water.

While preparing to make the film, Disney artists imagined the appeal of dancing patterns of light on the sand under clear, tropical seawater and we knew that capturing the beauty of water would be paramount. To reproduce this phenomenon in a realistic way, a technique was implemented called photon mapping which works by simulating the way light particles emitted from the sun scatter from the water surface and accumulate on nearby objects.

This was also extended to scale efficiently for vast oceans, emitting additional photons into the parts of the world that were seen more clearly by the camera. These techniques empowered artists with an automated way to generate caustics for the movie while still retaining artistic control over how they affected the final image.

2023 - Full 2D Stylization on 3D - Wish

While we don’t know much about Wish yet, the talk this afternoon mentioned this milestone. As the film has not yet been released, obviously detail was not gone into, but we were instead shown the trailer, which you can see below.

Walt Disney Animation Studios’ Wish is due to release on November 22nd, 2023. You can also catch many of the films mentioned in this list streaming on Disney+ or home releases where available.