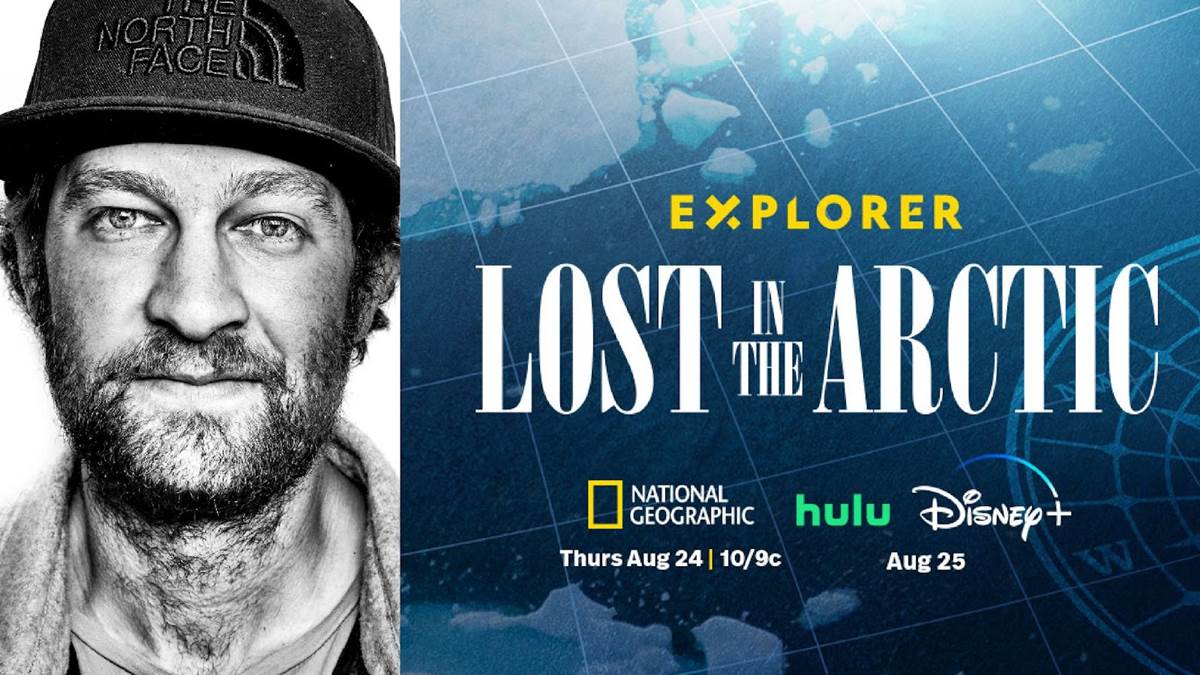

Interview: Filmmaker Renan Ozturk Discusses New Nat Geo Doc “Explorer: Lost in the Arctic”

Filmmaker Renan Ozturk recently joined National Geographic Explorer Mark Synnott on a mission through the Northwest Passage to try to solve the mystery of Sir John Franklin’s lost expedition. Franklin and his crew of 129 men never returned from their journey to map out the new trade route at the top of the world in 1845. Synnott’s mission is chronicled in the new Nat Geo film Explorer: Lost in the Arctic, which premieres tonight at 10/9c on Nat Geo, streaming on Disney+ and Hulu beginning August 25th. I had the honor of speaking with Renan Ozturk about the new film, which posed many unique challenges for the climber and filmmaker.

(The North Face/Nat Geo)

Alex: Congratulations on the new film. In some ways Lost in the Arctic feels like a companion piece to Lost on Everest. Obviously, you're looking for another lost expedition, but I understand your background is more in climbing. Did this feel significantly different since you were traversing water and marshland versus uphill surfaces?

Renan Ozturk: Yeah, it's completely different. Same vein, same model, same ethos of the trip. But this one was a lot more challenging going into the big ocean environment in a landscape as unforgiving as the Arctic and being on the water for months on end. I think the boat sailed 8,000 miles, and Mark and I had always dreamed about doing a big sailing trip. I grew up sailing a bit on the East coast, but never done a big ocean trip that was so self-sufficient as this, and it was Mark's own boat. So the fact that he was also the captain of the boat and we were the crew. Most film projects like Lost on Everest, we had a team of Sherpas, Tibetans, high altitude workers, yaks, producers, supporters, a team of five filmers. On this we had two people filming, and that wasn't our main job. Our main job was to be crew members of the boat to help Mark. We were more in-depth and over-committed than we had ever been on any one of these projects. And there were many times where I was like, "There's no way we're coming back with a film because all we're doing is looking out for ice on the boat, and that's the priority of staying alive." There are many, many moments that were missed, and we were really lucky to come back with what we did.

Alex: It looked really harrowing. What was the timeline of this? When were you doing the expedition? And it looked like a pretty seasick, nauseating voyage as well.

Renan Ozturk: Yeah, there are moments of seasickness, there are moments of calm, but it was four months, 8,000 miles. And there's a lot of different sections. We had Jacob [Keanik], our Inuit character with us on the main section, where we also got stuck in the ice. Narratively, it didn't make sense to put that in the main edit. It's not often that you do a trip that long, and that just speaks to our passion for these adventures. That doesn't happen in normal documentaries these days because we do a lot of docs, and often the network's like, "Oh no, we're only going to pay you per week, because that's our production schedule, that's the budget." But the way that we approach these things is as passion projects, and we're doing them no matter what. We're going to go the distance. And this is just a unique story. When else are you going to get a chance in your life to traverse over the roof of the world and experience the Arctic firsthand? I don't know if you're familiar with the term ground truthing. In science, there's one thing to have a hypothesis and do these things, but unless you're there speaking to people on the ground, experiencing it firsthand, and having the ground truth of what it's like in the Arctic, that's really the true measure of it, of what it's going to be and being able to share that through a film like this is the biggest opportunity of all. You're taking your ground truthing, and you're sharing it with a worldwide audience in all these ways, and we wanted to go all in for that.

Alex: As a climber, I’m sure you were already aware of the story of Sandy Irvine featured in Lost on Everest before that project came your way. Was the Sir John Franklin Lost Expedition on your radar before Mark Synnott proposed this to you?

Renan Ozturk: No, we always wanted to do a sailing trip from the East Coast up to Greenland to go climbing. And I think Mark stumbled upon this mystery because of how well-read he is as a writer and author. He just started reading every single book. And then he met Tom [Gross, Franklin Historian], who had been searching for 28 years and was so close to being able to solve it. It just seemed like such an amazing model and way into the Arctic and the story. For me, it was more than that. I was so curious as to the Inuit perspective of the North, much like I am with the Sherpas and the Tibetans on Everest. You always need a way to frame the narrative, and it was the perfect thing. I learned a lot along the way. And at first, to tell you the truth, I wasn't as into another dead white guy story. Do we need that? But in the end, the more I learned about them, and what they went through, there's something deeply kindred about it in the spirit of adventure that we all share. That was a beautiful thing to try to bring them home in a lot of ways do justice to what they went through, and write another chapter in their story.

Alex: This mystery is fascinating because we know about a missing piece of the puzzle that will answer all of the questions: the elusive captain’s journal. In the film, you guys find some artifacts from a potential campsite. Was it determined that they were actually pieces of this lost expedition?

Renan Ozturk: Yeah. Jacob, our Inuit character with us was like, "Yeah, Inuit could not have made these brass fittings for an engine or these tent pegs." So it was another lost camp, and we found that within a few days of searching the areas that Tom had identified. That was super exciting. And after that, it was like a crazy rabbit hole chase where everything kind of looks the same up there. It's the Midwest of the Arctic, where it's all flat, and it's hard to determine where you are. The GPS feels like it's playing tricks on you because you're so far north, and you're constantly getting lost. But it was really exciting to find those, and that confirmed that Tom's theory was correct and the way that their movements were and rewrote a little bit of what happened. That combined with the aerial surveys, that super high-resolution drone mapping, which is good for mapping for climate change and tundra, but also, I think that's the ultimate Where's Waldo for the future. So it's kind of like a big map.

Alex: I’m fascinated by the new technology being used in archeological excavations. In addition to drone mapping, there's also LiDAR. If you guys could get LiDAR up there, do you think you'd be able to find the exact location of Sir John Franklin’s tomb?

Renan Ozturk: I think it would help because you can 3D map a little more, and I think LiDAR penetrates a little more. It's just so far out there, the resources to mount a LiDAR on a drone is significantly more. This came up earlier, but it's like, why do this? And the funding to do it. There's not many organizations that fund these kinds of historical searches and expeditions. We're just lucky to have the support from Nat Geo and have enough history in telling these stories that somehow we can convince the budget to be unlocked to do these adventures and tell these stories. To get the support to go back to do LiDAR, I think it'll happen at some point. It's one of the biggest seafaring mysteries of all time, and it's only a matter of time before it's found, so that could be part of the next level of actually hiring maybe, I don't know if it's a heli or a fixed wing plane to do slow flyovers with LiDAR, do some next level mapping of that complicated island terrain.

Alex: That would be awesome. Mark Synnott's narration ties this story back to a human connection. These men had loved ones that never got answers about their fate. With DNA testing, they've even figured out who the bodies are that have been discovered and who their relatives are. As you announced this project, did you receive any interest from descendants or relatives who are eager for this mystery to be solved?

Renan Ozturk: Personally, I haven't. I think Tom Gross, who's been more entrenched in it in a longer period of time has probably talked to a lot of family members. Same as Everest, I think that's what we have in the back of our heads when we're doing these mysteries. It's the personal element. It's like, why does it even matter? If your relative died, the first question you're going to ask is, how did it happen? I want to understand what went on in those final moments. And it's a simple thing, but also really powerful and really human, and that's what ties a lot of these stories together and in really simple ways, and that's so brilliant about Mark's storytelling is he brings it back to that.

Alex: Thank you so much. I really appreciate your time. Congrats on the film, and I can't wait for the rest of the world to see it.

Renan Ozturk: Thanks, Alex. Yeah, have a good rest of your day.

Explorer: Lost in the Arctic premieres Thursday, August 24th, at 10/9c on Nat Geo. It begins streaming on August 25th on both Disney+ and Hulu.