8 Fun Things I Learned While Reading “Disney In-Between”

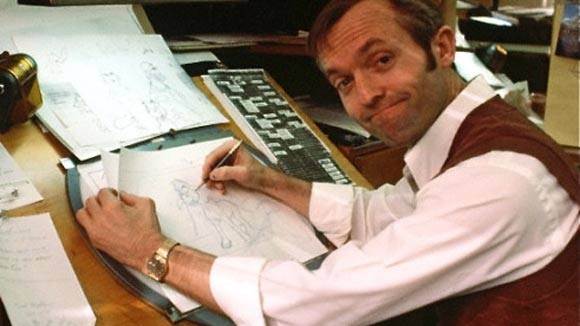

Stephen Anderson, known for his story work at Walt Disney Animation Studios as well as directing Meet The Robinsons and Winnie The Pooh (2011), is now telling the story of an oft-overlooked era at the Walt Disney Company in his new book, Disney In-Between.

Spanning the transformative era from Walt Disney’s 1966 passing to the studio’s resurgence in the mid-80s, under the visionary stewardship of Roy E. Disney, Michael Eisner, Frank Wells, and Jeffrey Katzenberg, Anderson uncovers the tale of how this once-independent, family-driven movie powerhouse, renowned for its innovation and forward-thinking, faltered amidst seismic disruptions.

The book features extensive interviews with the minds behind the well known films of the era (regardless of whether or not they were well-known for the right reasons) and also shines a light on a new generation of filmmakers and leaders, fueled by a love for Disney’s enchantment, yet unencumbered by its history.

Anderson covers a lot of uncovered territory in this era, sharing tons of information that even the most intense and well-versed Disney fans can learn something from. Here is just a small sampling of some of my favorite things I learned while reading the book (available now), with eight fun things I will remember after my first reading.

A PG-Rated Departure

Tim Burton is mentioned throughout the book, as he was a key player in terms of the animation department. However, as Anderson notes throughout Disney In-Between, the studio didn’t seem to know quite what to do with him. However, his time at the studio also led to a short film, Vincent, which was later followed up by Frankenweenie, a live action short (not the 2012 full-length stop motion feature of the same name). However, the film, which follows a young boy who sets out to revive his dead pet using the monstrous power of science, received a PG rating.

While that might not seem to be a problem in the Disney of today, the original plan was to attach the short to a re-release of Pinocchio - a classic G rated film. The more “risque" PG rating caused Disney to back away from their plan, and frustrated, Burton finally left the studio.

This Is A Halloween DCOM?

Further expanding that notion of Burton trying to find his place at the Disney Studio prior to his departure, one of the projects that he got to develop was a special for the Disney Channel, Hansel and Gretel. According to Anderson, “It was campy, it moved at a glacial pace, and was accompanied by the gentle piano music of Johnny Costa, composer for Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. Burton created something wholly unique and unlike anything made anywhere, let alone Disney." While the film aired on Halloween night of 1983, it was never aired again. However, Burton still wanted to realize more of his artistic endeavors, including one that would later define his aesthetic. He developed and pitched two more holiday specials for the network, Trick or Treat, which was written by Delia Ephron, and another based on his own short story, The Nightmare Before Christmas. The studio passed on both projects. This was 1983 - nearly a decade later, the full-length stop motion film, Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas would arrive in theaters, directed by Henry Selick and produced by Burton, put into production and released by Touchstone Pictures after Michael Eisner, Jeffrey Katzenberg, and Frank Wells arrived at Disney several years later.

A Brilliant Back-Up Plan

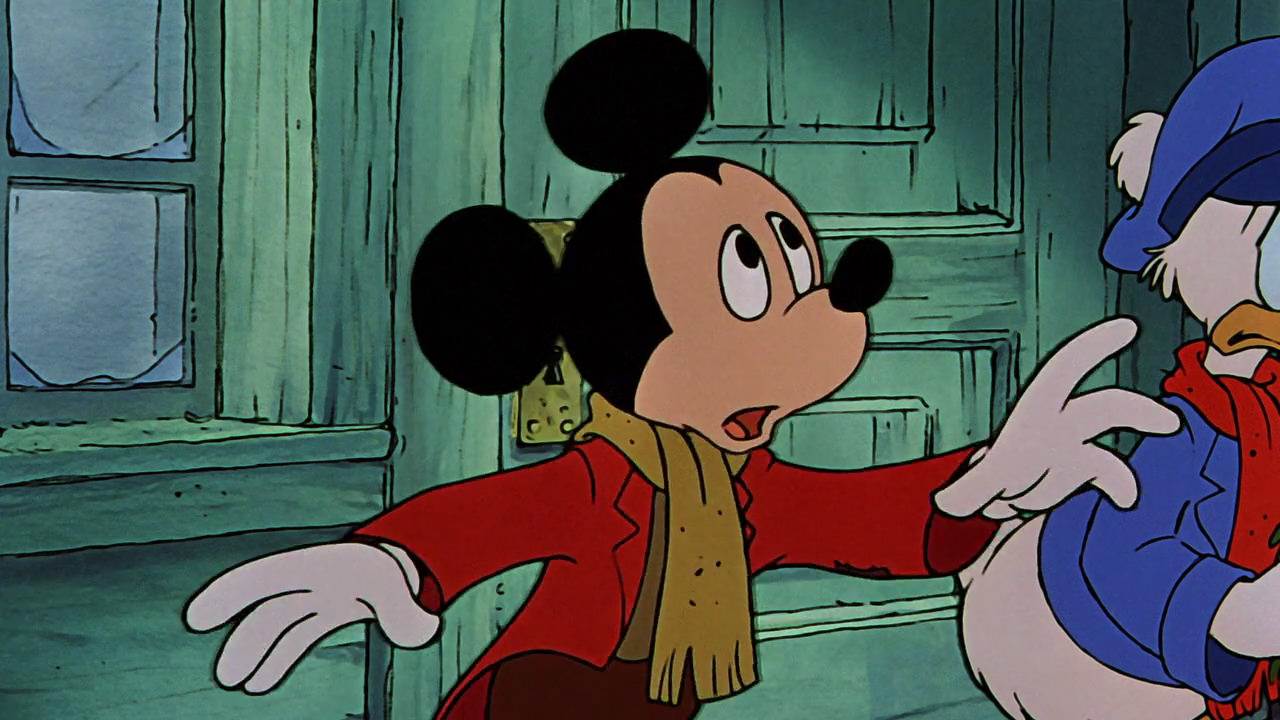

Disney Legend Burny Mattinson is widely known as Disney Animation’s longest tenured artist, and had his hand in nearly every animated project Anderson outlines in his book. Many know that Mattinson also helmed the popular animated short, Mickey’s Christmas Carol, but Anderson’s interview with Mattinson reveals that this project (though it was something he had long wanted to do) was pitched after an outburst with the directors of The Black Cauldron that he was certain would cost him his job.

Inspired by an earlier project doing freelance work - a storyteller record featuring Disney Characters in the Dickens classic, A Christmas Carol - Mattinson pitched the idea to then-studio head, Ron Miller. Anderson elaborates in the book, “Like Bob Cratchitt approaching Ebenezer Scrooge for a raise, Mattinson humbly stepped into Miller’s office. Miller sat at his desk that was perched on an elevated platform. His head was down, and he was writing intently. Mattinson sat and waited in silence until Miller finally stopped writing and glared down at Mattinson. “What in the hell are you sending me this note for?" he barked and threw the paper at Mattinson. Feeling he had nothing left to lose, Mattinson defended his suggestion. “Well, I think it’s a darn good idea," he said back to Miller, who burst into laughter. “I think it’s a great idea," Miller replied, unable to keep up his ruse any longer. He told Mattinson to start storyboarding it right away. Mattinson couldn’t believe his good fortune. Not only was his job at the Studio safe, but he was getting the chance to bring his dream project to life."

Basil and the Box Office

Fans of Disney Animation might recall the story of the renaming of “Basil of Baker Street" to what would eventually be known as The Great Mouse Detective. It’s a key point of contention that was showcased in the documentary, Waking Sleeping Beauty, as many of the artists and animators at the studio felt the title was unoriginal and uninspired. This prompted an anonymous staffer (at the time) to create a fake memo that went out saying that all of Disney’s classic animated titles were to be renamed - each to something equally as uninspired and perhaps more marketable. The memo included such fake titles as “The Girl With The See-Through Shoes" (Cinderella) or “Seven Little Men Help A Girl" (Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs).

While it was widely known that it was marketing who made this decision, Anderson explains in the book that there was a very specific reason for this choice - and it wasn’t because marketing thought “Basil of Baker Street" was too confusing for wider audiences.

Before Eisner and Katzenberg arrived at the Disney Studio, the duo had put a film into production at Paramount - Young Sherlock Holmes. In fact, this is part of how “Basil" got the greenlight in the first place, since the execs were already engrossed in that world by the time they got to Disney.

However, when the time came for Young Sherlock Holmes to open in theaters, the film underperformed, causing a panic as to whether or not anything Sherlock Holmes was commercially viable. “Basil Street" and much of the iconography on the poster, including the trademark hat and magnifying glass were pulled. All because they were indicative of Sherlock Holmes, which was now considered “box office poison," as director John Musker told Anderson in the book.

Bluth’s Return

Fans with a deeper knowledge of the Walt Disney Company (and the art of animation in general) surely recognize the name Don Bluth. An animator at the studio who was rising in the ranks before staging a coup that crippled production at Disney, taking a crop of animators to his own studio - later producing films like An American Tail, The Land Before Time, and All Dogs Go To Heaven.

The tension, which Anderson displays beautifully in the book, and bitterness is still retained to this day but some who were present at the studio at the time, but that was not the last time Bluth visited the Walt Disney Studio Lot.

Anderson reveals in the book that Bluth himself returned nearly forty years after he walked out, as he was preparing to write his memoirs, wanting to walk in the halls once more to get in the right frame of mind. There, he even had lunch with Ron Clements, among others, who were present at the studio during that time. Anderson put it best in the book, noting that time heals all wounds, and emphasizes that “regardless of the friction that surrounded Don Bluth, his talent,

passion, and contribution to the art of animation—at Disney and beyond—deserves respect and appreciation."

Walt Disney’s Total Recall

Anderson reveals in the book that In 1981, a college tour took place with the goal of showing off that tides were changing at Disney. This tour was created not only as a way of reaching a younger demographic, but also as a recruiting effort, emphasizing that the studio is changing and not just for children. As part of this presentation, a short film was shown that showcased the talent at the studio and projects currently in development at the studio.

Perhaps the most interesting title mentioned was Total Recall, which the film described as a “film noir of the future." This was almost a full decade before the Total Recall that eventually was helmed by Paul Verhoeven and starred Arnold Schwarzenegger. As Anderson says in the book, “Knowing how the movie turned out, it’s hard to

imagine that, in a different universe, it could’ve been a Disney film." The film was eventually released in 1990 by Carolco Pictures.

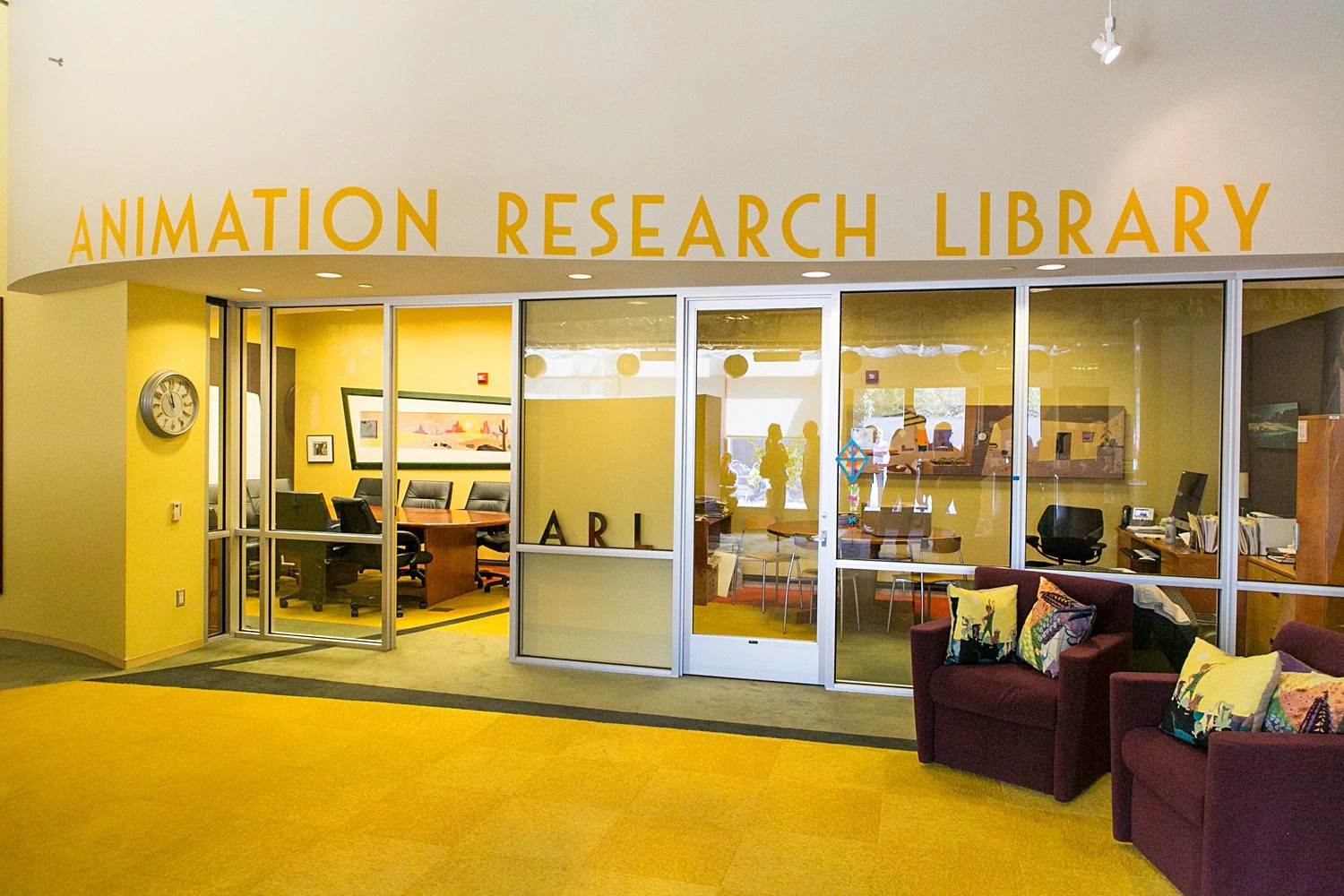

Hahn’s Hand In The A.R.L.

Disney Fans, especially of late thanks to social media and physical media bonus features are most certainly aware of the Animation Research Library. This facility, not a public one but oft used by the artists of the Walt Disney Animation Studios, is fully curated and preserves much of the art produced for animated films in its various stages. But it wasn’t always this way.

In the original animation building at the studio, was a room referred to simply as “The Morgue." Artists would check out animation drawings, but would not return them. Anderson reveals that it was actually Disney Legend Don Hahn, (known for producing Beauty and the Beast, among other Disney classics) who gathered a team in 1976 to launch an initiative to preserve and archive the artwork (some of which would get literally thrown away and pilfered from dumpsters by employees to make room for other assets). Hahn and the team would stamp dates, and scene and sequence numbers on each and every drawing, cataloging everything - with Hahn himself eventually hanging a sign on the door that said “Animation Research Library" so he no longer had to explaining to people what The Morgue was. As Anderson shared in the book, “the Animation Research Library (ARL) has grown to include over 65 million pieces of traditional animation art. They also keep an ever-growing collection of digital art, estimated at around 4.5 petabytes in size. Both the traditional and digital are housed in a state-of-the-art facility in Glendale, California. The ARL continues as a resource for Disney employees as well as museums and institutions looking to host exhibits of Disney

animation art and history."

Pete’s Easter Egg

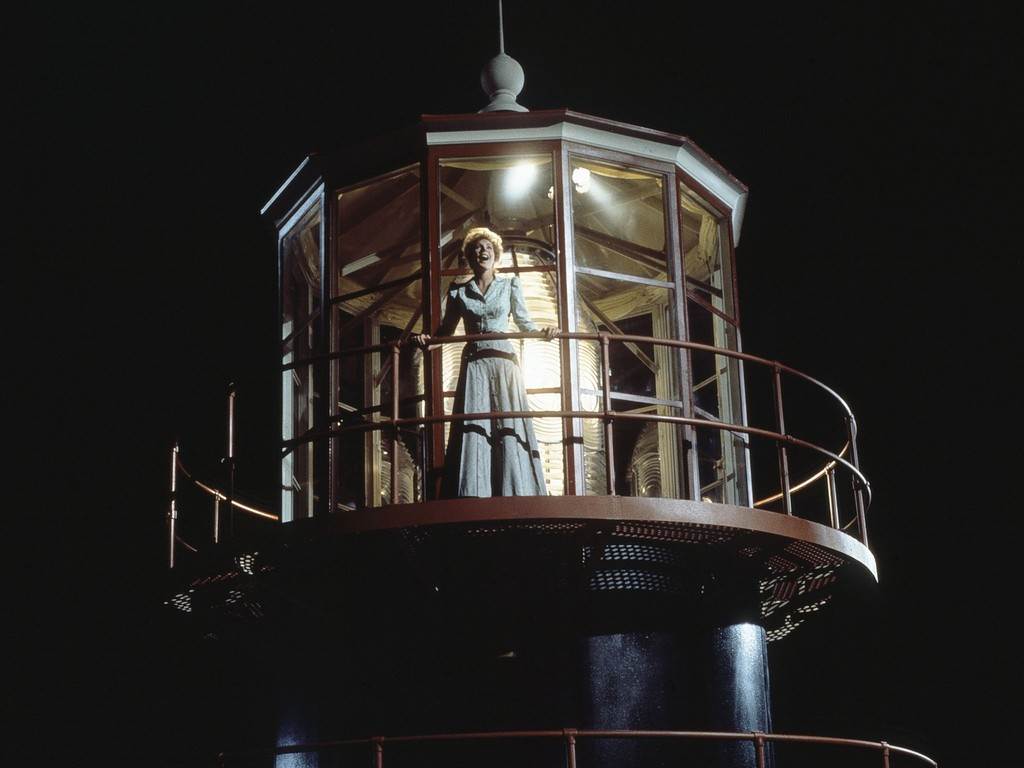

Al Kasha and Joel Hirschorn were tapped to write the songs for the classic film Pete’s Dragon. Previously, they had won Oscars for their work, so it was a great get for the production. Even though rock musicals were on the rise at the time, the duo stuck to their experience with the traditional “book" musical, bringing that expertise to the film. While the film has a number of songs, it’s “Candle on the Water" that is most widely remembered from the film. The song, a ballad for the character of Nora, is beautiful in the context of the film, as she sings out to her love who was lost at sea. However, the title is an easter egg hidden right in front of your face.

You see, Kasha and Hirschorn won Oscars for their songs featured in both The Towering Inferno and The Poseidon Adventure. When writing the songs for Pete’s Dragon, they gave a wink to these wins with the title, “Candle on the Water," “Candle" representing The Towering Inferno, (a disaster film about a skyscraper burning on its opening night with guests trapped inside) and “Water" representing The Poseidon Adventure (a disaster film about a cruise ship that is hit by a wave and rolled upside down in the ocean with guests trapped inside).

This is only a microscopically small sampling of what can be found and learned by reading Stephen Anderson’s new book, Disney In-Between. To get your hands on a copy, be sure to head over to the official site, here. For more with the author, be sure to check out our interview here.