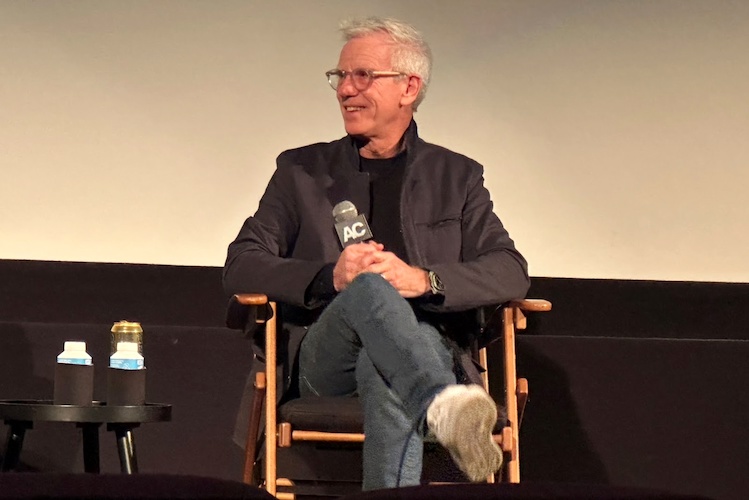

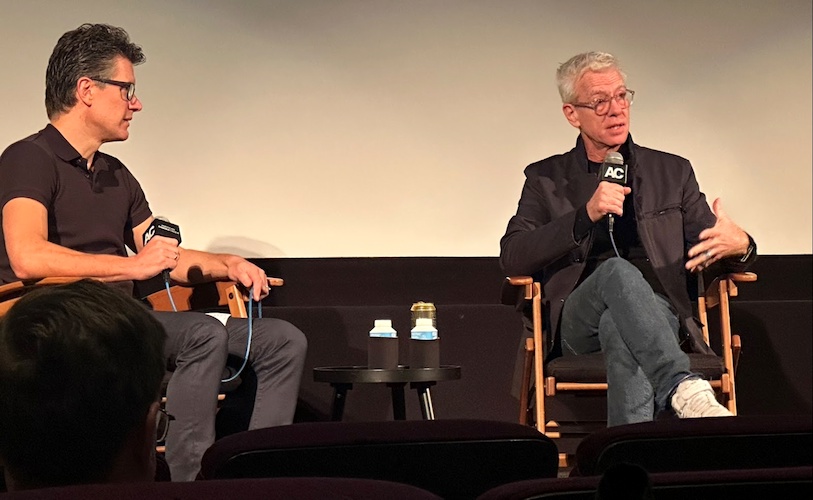

Director Chris Sanders on How Working on “Aladdin” and “Mulan” Impacted “The Wild Robot”

Chris Sanders’ impact on animation is rather staggering, which was underlined as many of his credits were listed off before he spoke following a screening of his latest film, The Wild Robot, at an American Cinematheque screening Friday night. During his early years at Disney, Sanders worked on – and got a Story credit on – some of their most beloved and popular films, including Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin and The Lion King, before receiving his first full writing credit on Mulan. His directorial debut was Lilo & Stitch, and he then went on to write and direct several films for DreamWorks Animation, including How to Train Your Dragon, The Croods and now the highly acclaimed The Wild Robot - the latter marking his first time as the sole credited writer and director on a film.

American Cinematheque was also screening How to Train Your Dragon that night following the Q&A and moderator Anthony Breznican noted both that film and The Wild Robot were based on books. When he asked Sanders if there were any lessons he learned adapting Dragon that came in handy with The Wild Robot, he said an important one went back to Mulan. This was something Sanders referred to as a “short circuit" - basically when you are over-complicating a film and its protagonist with two many overlapping motivations or obstacles.

With Mulan, he noted in early drafts, the title character was incredibly resistant to the arranged marriage she was headed towards when we met her, which was originally half the reason she leaves and disguises herself as a man to join the army - not just to take her father's place to protect him. This was something Sanders came to realize he and his collaborators were intent on including because of their own cultural beliefs they were putting upon Mulan and the Chinese legend they were basing the film on, initially feeling she should reject the idea of arranged marriages all together. As Sanders put it, “The story is really about a girl who loves her father so much that she's willing to risk her life, her reputation, her family's honor, because she puts such a premium on his life. And the problem was that when she left to take this place and disguise herself, there was not one reason she was leaving, there were two. She was actually getting out of this situation that she was unhappy with."

Ultimately, Mulan remains intended for an arranged marriage in the early scenes, “But we reconciled it by saying she's going to go to the matchmaker and she's going to try her best but It doesn't mean she's good at it - she messes it all up. So it's still fun, and it still ends in a way that's entertaining. And again, she's not really cut out for this whole thing, but she tried really hard and she was being very true to everything that she believed in. So when she left, she left for one reason, and suddenly the story started working."

With How to Train Your Dragon, Sanders noted he joined the film after some early work had already been done and looking at the early story reel and the book, he felt there was a contradiction hurting the film - “Vikings are fighting with dragons, but they're also collecting dragons eggs and hatching them and raising them. So that's two different things happening and you've got to have just one." The decision was made to drop the dragon egg aspect of the story.

Sanders stressed that these sort of differing elements can work in a book, which simply have more time to tell their story. But in animated films, “we always have a time limit of around 90 minutes. It's just what our budgets can sustain and our production can sustain.“

When it came to The Wild Robot, the big change wasn’t so much about the overall story arc but about removing a notable supporting character from the book - Chitchat, the squirrel. In the book, he’s a fun and funny character who can’t stop talking, and thus receives many pages of dialogue. Making the film, Sanders felt the character was upending the narrative, “because the moment Chitchat arrives, it really becomes just about Chitchat and [the title character] Roz would just disappear from the moment, and we didn't have a lot of screen time."

Sanders said most people have accepted this explanation but that when he spoke after a screening of the film in San Francisco, there were many kids who’d read the book in attendance and after one asked “Where’s Chitchat?" and he explained why he cut him, the next kid who asked a question then also asked “So where’s Chitchat?," making Sanders think “I’m not going to get out of here alive."

Looking back on his career and how it had led to The Wild Robot, Sanders talked about the trope in a lot of Disney animated films of absent (which is to say usually deceased) moms. He noted when they were making Aladdin, Aladdin’s mother originally was alive and present. However, that proved a story obstacle, since first off, she’d probably be doing her best to curtail his thieving ways, and then once he went on his adventure with Genie, they were spending screen time going back to her worrying about him and it felt like it was impeding and slowing down the central storyline. With The Wild Robot and its central story of the robot Roz becoming an adoptive mother to the goose Brightbill, “The idea that the story was centered around the mother was very exciting to me because that's the thing that was always just not there."

Following in the footsteps of The Bad Guys and Puss in Boots: The Last Wish, The Wild Robot is another DreamWorks animated film that has moved away from a traditional CG animated look for something more painterly and impressionistic. Pondering the appeal of making animals in animation not look photorealistic, despite having the technology to do so, Sanders said he felt it came down to how art engages a different part of your brain. He also said he felt that sometimes photorealistic animated animals can look a bit too perfect, “like they just came out of a salon. Even though they have a photo-real sort of thing going on, there's also something that's a little bit cartoonish, because a fox wouldn't look like that in the wild. So there's a thing that's fighting the believability, in a way." When working on The Wild Robot’s fox character, Fink, and putting him into this more painterly style, Sanders said they discovered, “The overall impression is that he's more real."

Sanders felt the visual style of The Wild Robot is one of the reasons the film has the impact it does, adding he personally has never felt the way he does about The Wild Robot compared to other film he’s worked on and that despite seeing it hundreds of times working on it, he keeps going to see it. He added, “In fact, I think I’m gonna go out this weekend and see it a couple more times, because I'm not sure how much longer it's gonna be in theaters and I just want to see it a few more times."

More on The Wild Robot: