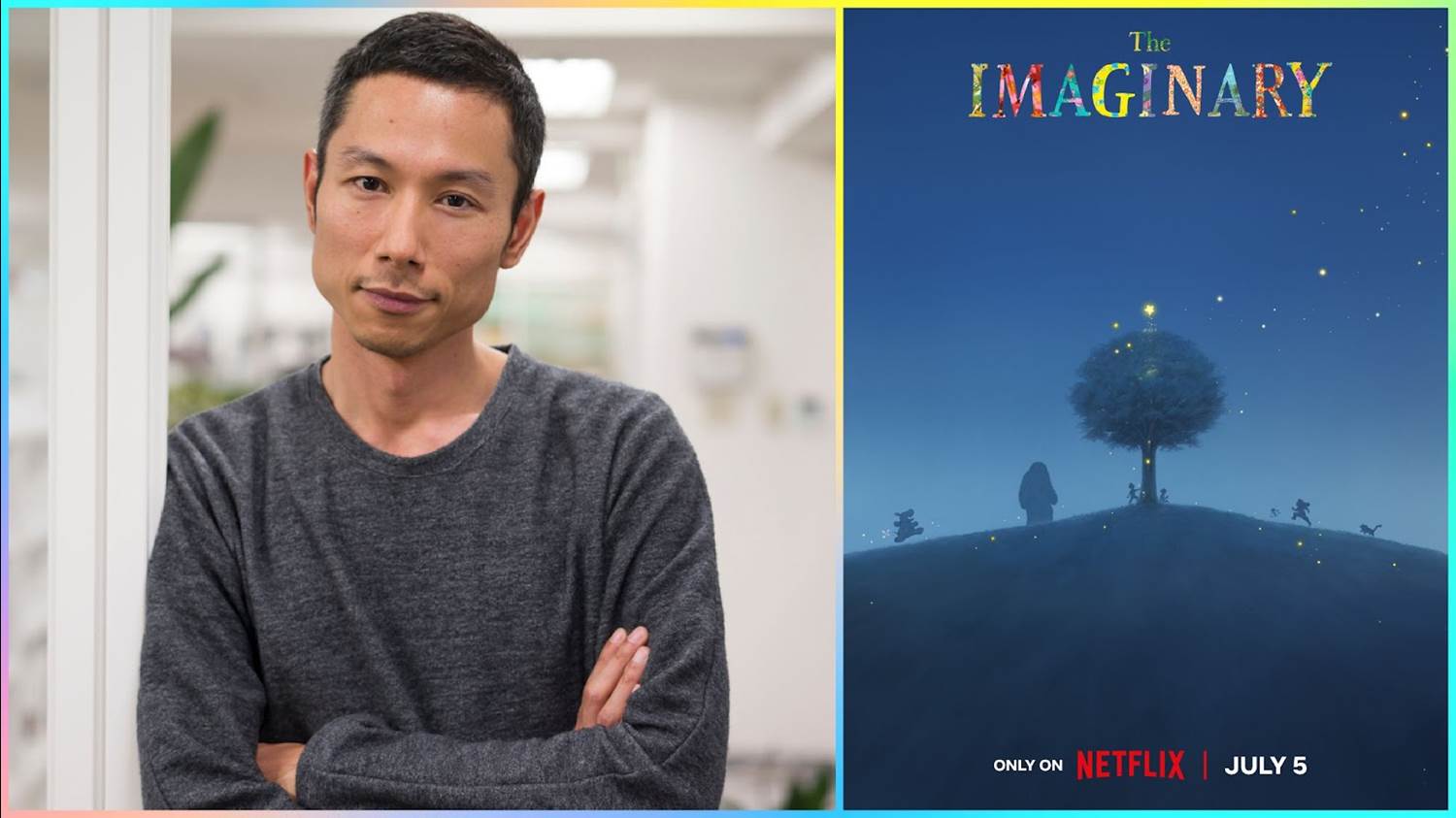

Interview with “The Imaginary” Writer/Studio Ponoc Founder Yoshiaki Nishimura

The rich legacy of Studio Ghibli lives on at Studio Ponoc, founded by producer Yoshiaki Nishimura in 2015. The studio’s second full-length feature, The Imaginary, already wowed audiences in Japan and is about to take the world by storm. Adapted by studio founder Yoshiaki Nishimura from a book by A.F. Harrold, the film held it’s English language premiere at Annecy Festival ahead of today’s premiere in select theaters. It will soon stream globally exclusively on Netflix beginning July 5th. I had the honor of speaking with Yoshiaki Nishimura about The Imaginary and how this hand-drawn animated film pushes the boundaries of the medium with cutting edge technological advancements.

(Netflix/Studio Ponoc)

[NOTE: This interview was conducted through a translator.]

Alex: When was your first exposure to A.F. Harrold's novel, which inspired the film?

Yoshiaki Nishimura: We discovered it about six years ago when we were making three short films. We frequently look at children's books from not just Japan but also Korea, Germany, the UK, and the US. I found a very intriguing book in a bookstore, and the cover illustration by Emily Gravett was so wonderful that I picked it up and read it. The unique setting immediately captivated me.

Alex: You worked with director Yoshiyuki Momose at Studio Ghibli, and he previously directed a short at Studio Ponoc. Why was he the right choice to direct The Imaginary?

Yoshiaki Nishimura: I joined Studio Ghibli in 2001. Like many around the world, I thought of Studio Ghibli as being run by Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, who were very visible outside of the studio. When I started working there, there was one person with a private glass-walled office, which was unusual. I asked who it was and learned it was "Momose," written in kanji as "Hundred Room" [Both “Momose" and “Hundred" in kanji contain the same character - 百]. It turned out that Mr. Momose was highly respected at Studio Ghibli as a third key figure, known for expanding Studio Ghibli's expressive capabilities in terms of styles and techniques. He was the first in Japan to use computer graphics in animation, and his innovative techniques, like using computers to create rolling wave flows on water, were pioneering. I was deeply fascinated by his talent. After working at Studio Ghibli for over ten years, I always wanted to make a film with Mr. Momose when I had the experience and position to do so. With this project, that dream came true. I thought this film was perfect for him.

Alex: This film's colors are distinctive, with soft pastels that feel vibrant. Can you explain the approach to color in The Imaginary?

Yoshiaki Nishimura: Mr. Momose has always liked pastels. As a production, we were looking to capture a storybook quality with soft lines, which is difficult in hand-drawn animation. I came across a demo by a French animation studio. It was a short reel, but the technique that I saw really captured what we were looking for. It had a way to play around with texture, light, and shadow and create a different depth to what we were doing already. I quickly brought this to Mr. Momose's attention, and he agreed it could achieve the soft visuals he desired. It increased our capacity to adjust the lines that we were drawing so that it had that softer storybook look Mr. Momose desired. It added aesthetics, and the technology allowed us to delve deeper into human emotions and create more realistic psychological portrayals.

(Studio Ponoc/Netflix)

Alex: You talked about shadows and character lines, but The Imaginary also handles light and reflections in a way that feels different from other hand-drawn films. How were those effects achieved?

Yoshiaki Nishimura: Replicating light reflections in hand-drawn animation is indeed challenging. In CG, it's relatively straightforward because you can move the model and see the reflections in real time. However, with hand-drawn animation, everything is flat. We create the animation up to the coloring stage, where most animation productions would consider the scenes complete. Then, a French studio named Les Films du Poisson Rouge takes our colored backgrounds and characters and does a preliminary composite. They add the lighting and shadows, which are then sent back to us for final compositing. This was a complex, time-consuming process. It was actually quite reckless because we don't speak French, and they don't speak Japanese. We even had a lighting director, which is unusual for Japanese hand-drawn animation. A talented person named Anaël Seghezzi from the French studio helped us significantly with this. It was a big challenge, and we have been told that adding digital shadows to hand-drawn animation is difficult because it’s a flat surface, so it’s not as exact as it would be on three-dimensional features. But Anaël was very familiar with the work of Studio Ghibli, so they were able to communicate through art. It was very technical and complex.

Alex: Music has always played an important role in Studio Ghibli's films, with famous composers like Joe Hisaishi. What role does music play in Studio Ponoc's films, and specifically The Imaginary?

Yoshiaki Nishimura: I love film scores and listen to them a lot, in addition to classical music. Music in a film helps create its image and enhances the director's vision. Scores can help define a director’s body of work. Music was particularly challenging for The Imaginary because Mr. Momose has a wide taste in music, making it hard to pinpoint a clear direction. Additionally, the script I wrote already had specific pieces of music in mind for different scenes. The thing about cinematic music is that we need to think about whether that choice is being made purely by the filmmaker or whether it is something that is actually internal to the characters, especially in this film because many scenes are set within the characters' imagination. For example, if we are in the imagination of Amanda, who is playing the music? Where is it coming from? Is it just playing within Amanda's head, and is everything generated by Amanda, or did filmmakers make a choice prior to the scene? That applies to all the different characters as well, not just Amanda, whether it be John or Julia. So there will be different tastes and different types of music. It wouldn't be just one. It was very difficult to come up with one unified style, which made it harder to decide on the final score. Instead of hiring a film composer, we worked with a music producer to ensure a cohesive soundtrack that matched the film's various imaginative scenes.

(Studio Ponoc/Netflix)

Alex: The film has already been released in Japan and will soon be launched globally on Netflix. How was the reaction in Japan? Were Studio Ghibli fans enthusiastic about it?

Yoshiaki Nishimura: Studio Ghibli fans did come to see it, and many people watched it. The responses were very enthusiastic. Some elements of this film seem to speak to people more deeply than we anticipated. It probably applied to a lot of Studio Ghibli works, as well, but rather than a very direct reaction, what I saw at the initial screening was some high school students who came out of the cinema and really just stood there. They couldn't say anything. They were trembling. When I saw that, I was like, oh, maybe this film has the capacity to touch the innocent part of people that we forget about as we age. Perhaps it had something to do with the visuals of Lizzie, Amanda, Rudger, those characters, but different elements depicted within the story seemed to speak to people, not just as fictional stories, but added the realistic elements that they could draw a parallel between. That seemed to generate reactions from a wide range of audiences. This film has that kind of quality that speaks to people on a really deep level. And just to touch on the partnership with Netflix, this film will be launched in 190 countries, and Netflix has around 300 million user accounts. Those numbers may seem huge and may mean something to people, but what I really want to achieve is not so much on the sales figures or the number of views, necessarily. It would be an honor if this film could speak to one particular viewer in a personal, deep way. That would mean something to me. I remember watching Isao Takahata's work as a child, and I felt like his films were made for me. They spoke to me on that level. If I could achieve that through this film, as a filmmaker, I can't think of anything better.

The Imaginary is now playing in select theaters in the United States. The film will be available to stream globally beginning Friday, July 5th.

(Please note this article contains affiliate links. Your purchase will support LaughingPlace by providing us a small commission, but will not affect your pricing or user experience. Thank you.)