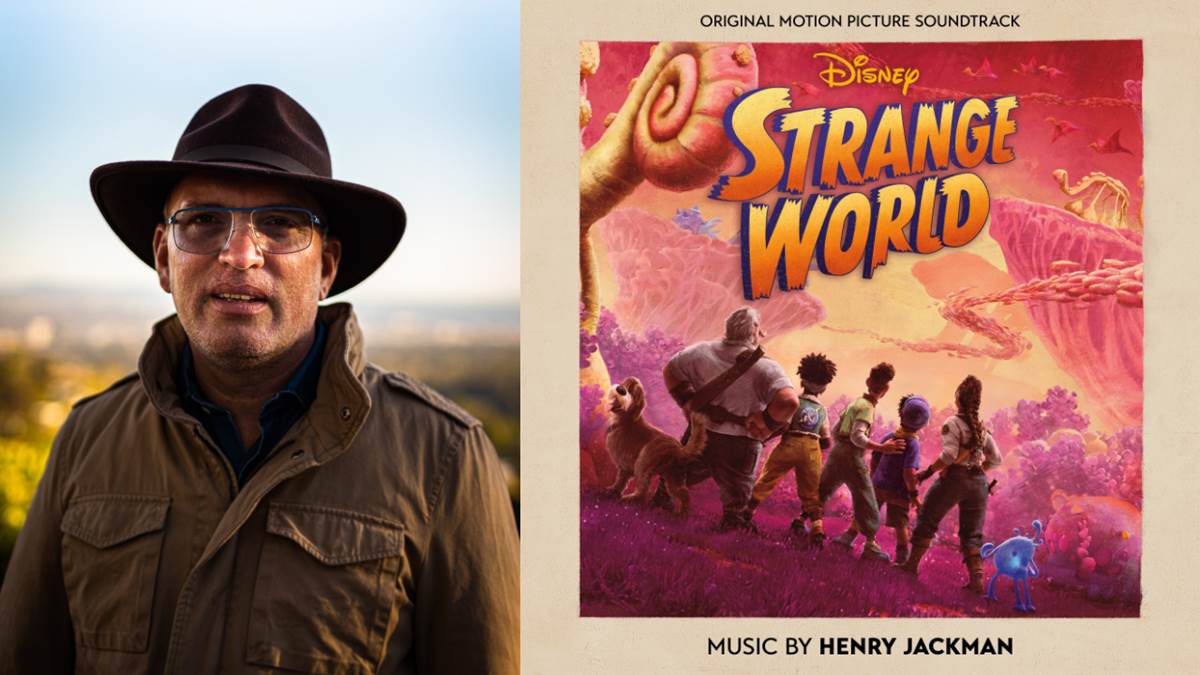

The story and out-of-this-world visuals of Disney’s Strange World carry audiences to a fantastic realm full of endless possibilities. But the journey for moviegoers wouldn’t be as exciting with the sweeping score, created by Henry Jackman. I recently had the pleasure of talking to Henry about his approach to the score for Strange World, how you create music for an amorphous blob like Splat, and why comprising for Walt Disney Animation Studios is so special.

Benji Breitbart: Strange World has a very epic scale and a very sweeping symphonic soundtrack. Can you talk about your approach to the musical language of Strange World?

Henry Jackman: I was just finishing The Gray Man, and I'd read the script. I thought it was a unique opportunity. I was super excited about Strange World because the ambition of the film had to be matched by the music. One of the huge components of the film is this giant epic exploration of a brand new world, as it were. And to that extent, it almost has a lineage of classic films like Journey through the Center of the Earth or Indiana Jones or anything that has that slightly exotic feel and really needs a feeling of mystery and exploration. So I really wanted to come up with an idea for Strange World that reflected that combination of mystery and wonder. And funny enough, I'm a great believer in order to really feel mystery, you shouldn't feel safe. It has to have some harmonic and melodic language that's sort of inspiring and wondrous, yes, but should also be fractionally unsettling. Because I don't really feel that you can feel true awe or wonder if you're not simultaneously feeling unsafe. I remember towards the end of The Gray Man, I was on the piano coming up with these little sequences of arpeggios that were like a bad version of Debussy gone mysterious. And I was just fiddling around, and I almost didn't really know what I was doing, it was a bit subconscious. And it took me a while to actually analyze, the harmony was quite unusual. Without sort of telling anyone, I wrote this four minute or three-minute piece, which shows up on the soundcheck actually. It's towards the end, I think I just called it the “Strange World Overture.” So I wrote this piece away from picture, just called it the “Strange World Overture” and it starts small and it's just this rather grand, almost classical, quite sweeping, it definitely has classical music influence. I mean, I'm never going to be as good as the real composers of history, but it had an influence of maybe a bit of Strauss and Debussy, and it was quite lofty in its intention. At the time of writing, I was thinking, "Wow, this is either pretentious and useless or it could be useful. Let's see." So I finished the piece and orchestrated it all. And then I played it to the directors and said, "Feel free to react however you want. Here's this piece called ‘Strange World Overture,’ which I think may have something to it. It's sort of epic and it has a sweep to it, but let's see what you guys think." And to my huge relief, they absolutely loved it, which I was a bit worried that it was not quite… I don't know. It's funny, when you go into isolation and write a piece without talking to anyone, you always have the fear that you're disappearing down a rabbit hole. But as I say to my huge relief, Don [Hall] and Qui [Nguyen] said, "This is exactly how we imagined Strange World could sound and more." So I mean, that was the ultimate compliment. I think I just struck it lucky there. And as I say, it was a combination of slightly unusual harmony and a slightly angular melody, but of huge orchestration. The whole film isn't the Strange World theme, but that was my route into it because I just felt like this exploration of another world was such a central part of the filmmaking, because Don and Qui are really smart and they're great book writers, it's not just that, it's this huge epic unexplored world, but it's also a family story. So throughout the film, you get moments of great intimacy and emotion, and you also get great epic reveals of this unexplained world. So it has a bit of everything, and that also got reflected in the music. My route into the film was to write an overture away from picture, not for any specific scene, to see if I could just dig into the overall mystery and epic scale and symphonic lushness of what Strange World should feel like. Because if they like that, then it's as if you've got the DNA that's going to help you describe the film once you get to the individual musical moments.

Benji: Choir vocals add a lot of color to the score. What were your goals with that decision?

Henry Jackman: I've always loved choir. As it happens, I was actually a chorister at St. Paul's Cathedral when I was between eight and twelve years old. That's a very different kind of music, mostly. That was cathedral liturgical music sung in the Christian services and whatnot. But nevertheless, there is a connection there in as much as choral music is significant that it's often thought of in the context of religious worship. And if you think, regardless of whether you have a faith or not, clearly the idea is to sort of elevate the spirit and make you feel, put you in mind of things that are not ordinary, not part of everyday life and to try and transport you into another world. Now, it's not to say an orchestra can't do that or any number of instruments can't do that, but there's no denying across all sorts of cultures that choir and the use of choir and the human voice can have a transporting effect, particularly to sort of put an audience in mind of something not of this earth. So to that end, quite often the choir was used for that purpose. And in addition to recording the fantastic choir that we used in Los Angeles, just to give it that extra unearthly edge, we would record the choir and then also I combined it with a synth choir that didn't quite sound as realistic as a regular choir. Had a slightly, I don't know what the word would be, maybe more mysterious, maybe more abstract sound that sort of combined the real choir with the synth choir just to sort of… A bit like an augmented reality maneuver, choir plus an extra unknown texture that goes with it that was also choral but more abstract. And I think that helped contribute to that slightly intangible feeling of mystery.

Benji: You can't have a Disney movie without a really cool sidekick. You previously worked with Baymax on the score for Big Hero 6, and this film introduces Splat. What is his musicality like?

Henry Jackman: That's a very interesting question because in line with my previously described intellectual pretensions of trying to be as highbrow as possible and in the spirit of, let's say, a John Williams score, something like that. But I hesitate to compare myself to the great John Williams because we all fade into insignificance compared to the maestro. But just meaning in terms of the consistency of leitmotif and whatnot, when it came to Splat, I thought if I was any good at my job, instead of just coming up with any old idea for him, it should somehow be derived from Strange World. If you listen really carefully to the Strange World melody, in that piece, I was describing on the soundtrack called “Strange World Overture,” I actually took the notes of the melody, and then I made them a lot shorter and truncated it. I sort of took it and truncated it, changed all the orchestration, gave him a sort of slightly odd combination of a microphone and pizzicato and these sort of playful textures. But actually, whilst the orchestration of Splat is in keeping with a lot of playful characters in the history of Disney Animation, the actual melodic material that's used for Splat is directly derived from the Strange World theme. And that might sound pretentious, but I felt it was quite important to have that kind of operatic consistency. If you have a giant theme to describe Strange World in general, then if the film score means anything, you ought to try to describe the entities of Strange World in some way derived from this overarching theme and find new permutations and combinations by truncating and accelerating the theme and changing all the orchestrations. So it's unrecognizable for the big sweeping theme, but underneath, under the bonnet, it's actually made out of the same Lego.

Benji: You’re no stranger to animation, having written scores for Winnie the Pooh, Big Hero 6, and Ron's Gone Wrong. Can you talk a little bit about what makes scoring for animation special?

Henry Jackman: A couple of things come to mind that are not exclusively true of animated films, but are often true. When you have filmmaking that is contemporary, realistic, psychological, and non-fantastical, it's not always true, but you tend not to have such classical use of motif and theme. To take an extreme example, the quickest way to ruin a fantastic Paul Greengrass film, and his filmmaking style almost has a documentary edge to it, it's very realistic, very realistic dialogue; that's not the time to deploy giant, sweeping symphonic themes. It would be completely inappropriate. Whereas, and it's not always true, but in animated films, there is more of a tradition of encouragement for melodic and symphonic material to be quite present. The word invasive is probably too pejorative, but the opinion of music is welcomed. You need it there, you want it there. In the same way that if you see the dinosaurs for the first time in Jurassic Park, it would be a huge disappointment if you didn't have an enormous reveal of a big theme. Of course, that's what you want because it's that kind of filmmaking. And that would not be true of other kinds of much more realistic down to earth filmmaking. So I think it's probably generally true that in animated films you will be caught short if you don't have a… For example, in Strange World, there's the Strange World theme, there's an Avalonia theme, there is a Callisto theme. And they're committed. Jumanji is not dissimilar in there being a need for commitment. And one is encouraged. You get sequences and scenes that demand big expressions of orchestral themes. That's not to say, obviously there are some live-action films, that's also true. I mean, I've just mentioned Jurassic Park, but there are probably more cases of live-action films where that isn't the case, and you might need a more minimalist, more textural sort of film score. So that's one thing. Another thing that's probably universally true is the speed at which story moves and the extent to which you need to shift the narrative in the piece of music. So for example, you might have a four-minute cue in something, a movie like The Gray Man where the psychology of the music is kind of similar for the four minutes, there might be a couple of important things to hit in the scene. Whereas if you look at a four-minute piece of music in an animated movie, it's more likely that you have 6 or 7, 8, 9, possibly 10 changes. It could have the need for tension at the beginning, and then it cuts to something else, and then there's a heroic outburst, and then it cuts to something else, and then you might be with Splat and Ethan for a bit, and then it cuts it. And so, the need to pirouette thematically and be able to maneuver with as much grace as you can muster from one scene to another or morph and transform the psychology of the music to express one thing and then possibly another, maybe a range of different ideas, I think that range in animated movies, the requirements are likely to be higher over the same period of time than live action.

Strange World is now playing in theaters. You can hear more of Henry Jackman’s music on the Strange World Original Motional Picture Soundtrack, now available from all major streaming music providers.